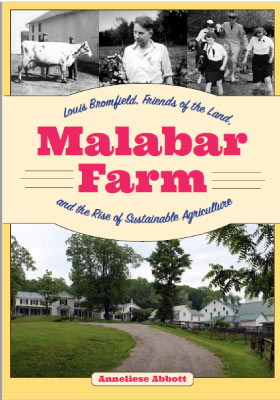

In 1939, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louis Bromfield moved to a rundown farm in Richland County, Ohio where his new, sustainable farming methods transformed the land into “the most famous farm in the world,” and changed the future of agriculture. The new book, Malabar Farm: Louis Bromfield, Friends of the Land, and the Rise of Sustainable Agriculture by Nelson Institute graduate student Anneliese Abbott, explores this history as well as what it can teach us about common ground, and the future of agriculture.

Abbott began developing her book as a part of an undergraduate honor studies project while she was attending The Ohio State University. Having grown up on a small farm, Abbott had always been interested in agriculture and, as a plant and soil science student, she was looking for a project that would focus on those areas.

“I went to The Ohio State University to study sustainable plant systems, because I figured plants are the most important part of agriculture. You can’t have animals without plants, so plants must be the most important,” Abbott said.

“One of the reasons I wanted to write this book and I want this information out there is so that people can learn from what worked and what didn’t. I want them to be able to avoid past mistakes and see why things didn’t work and whether we’ve addressed the reason why it didn’t work.”

A curator at the university recommended that Abbott review their special collection on Louis Bromfield. At the time, she didn’t know who Bromfield was, but through her research, Abbott discovered that Bromfield’s work on Malabar Farm was not only transformative and influential, but very close to what is currently known as sustainable agriculture.

“He was doing all of these things that we are just doing now,” Abbott said. “That really intrigued me to see that all of this was happening then. So, why do we think it’s new now, and what happened?”

To answer these questions, Abbott decided to take her final project a bit further. After graduation, she spent an additional four years studying Malabar Farm, Bromfield, and the history of sustainable agriculture, which at the time was called soil conservation or permanent agriculture.

She studied the agricultural methods used, the connection between farming, soil erosion, and the Dust Bowl, the New Deal, and the conservation group, Friends of the Land. Through her research, Abbott says she wanted to discover what the past can teach current farmers about the success of sustainable farming methods.

“These ideas are not necessarily new, so I think the current sustainable agricultural movement could learn a lot from going back and looking at its history and seeing that people were saying the same thing 70 years ago,” Abbott said. “One of the reasons I wanted to write this book and I want this information out there is so that people can learn from what worked and what didn’t. I want them to be able to avoid past mistakes and see why things didn’t work and whether we’ve addressed the reason why it didn’t work.”

Abbott also hopes that her book will showcases the ways in which Bromfield’s methods brought conventional and organic farmers together.

“Another reason I wanted to write this book is related to the controversy that we have in agriculture, the animosity between environmentalists and conventional agriculture,” Abbott said. “The sustainable agriculture movement tries to bring them together, but even that movement has become divided, especially when it comes to organic or regenerative farming. What’s interesting about Malabar Farms is it predates the controversy. There wasn’t this divide between what we would call conventional and organic agriculture like there is now. You can trace a lot of things from conventional agriculture to what Louis Bromfield promoted in what he called his New Agriculture, and you can also trace a lot of organic and sustainable agriculture to that New Agriculture as well. There was a divergence that happened in the 1950s and I think we could benefit from looking at Bromfield and trying to take a middle ground on a lot of these issues.”

Abbott’s book was officially published in December 2021, but she is continuing to study the history of sustainable agriculture through her Environment and Resources master’s program.

“In a way it was this book that led me to Nelson,” Abbott said. “I had finished it before graduate school, but the reason I applied to Nelson was this book got me interested in environmental history and the history of sustainable agriculture. It’s an interesting topic because it’s agricultural and historical and finding a program where I could do this research was why I was so interested in the Nelson Institute, it’s so interdisciplinary.”

Abbott will complete her master’s in May 2022 and is planning to pursue a PhD. She hopes to become a professor someday, but for now, she is enjoying her research and focusing on ways she can connect to agriculture.

“I want to stay connected to soil, no matter what I do. I don’t want to get off into the intellectual parts and forget about my connection to the soil,” Abbott said. “I’ve learned it’s actually the most important part of agriculture, because you can’t have the plants without the soil.”

Learn more about the Environment and Resources MS degree and how you can support the program.