In 1960, Jane Goodall made discoveries about wild chimpanzees by observing them on the ground through binoculars. Today, satellite technology is helping us observe changes in the land and ensuring the protection of chimpanzees where they live.

Highlighting the Jane Goodall Institute’s (JGI) people-centered conservation model, “tacare,” Dr. Lilian Pintea, vice president of conservation science, presented at the Weston Roundtable lecture series in September. A reflection of his work and on 10 years of environmental conservation at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Pintea told a story of people, animals, and the power of data that has helped make the JGI so successful.

Satellite Data Gives Us a Unique Perspective

A picture is worth a thousand words, and satellites take pictures of every part of our world nearly every moment. For the JGI, the message was shocking and undeniable — that chimps were essentially living on an island of forest surrounded by agriculture. Satellite data showed a clear boundary between Gombe National Park, a primary chimpanzee habitat in western Tanzania, and the surrounding lands where the forest was cut down to provide resources and land for local people.

It was this remote perspective that highlighted the importance of involving humans in the work to protect chimpanzee habitat. Chimps needed more forest habitat, and reforesting the area required working with the local people. Thanks to these efforts — and satellite images to measure the change — forests have been restored and chimpanzee habitat is increasing.

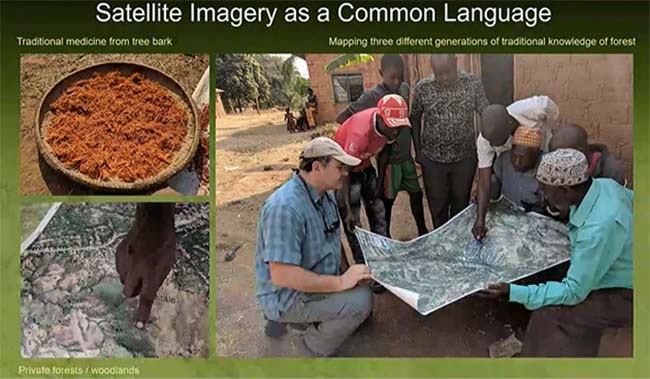

Satellite Data Shows the Human Experience

Any phone mapping app lets you look at a high-resolution satellite photo. The reason for that is simple. We can understand what we see in those photos because they show us familiar objects and features: our house, with its long curvy driveway; the oak tree at the intersection near the school; even the green hue of the lake in the summer because of algae.

Satellite data shows what you can see — the lakes, the trees, the roads. It also shows what you cannot see — the value humans place on specific locations and the patterns of their daily lives. Knowing where and why people value the land is critical for conservation.

The JGI’s work to protect and increase chimp habitat was only possible by interacting with the communities. Satellite photos were a powerful tool to work with the community and understand what they valued and why. The satellite photos acted as a common language. The people could point to what they value, and the scientists at the JGI could make a data point of that location. This information allowed JGI and the community to work together on planning chimpanzee conservation.

This lecture was part of the Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment’s Weston Roundtable Series. The lecture series features speakers who promote a robust understanding of sustainability science, engineering, and policy.

- View Dr. Lilian Pintea’s lecture: Local Voices, Local Choices: Insights from Community-Led Conservation Using the Jane Goodall Institute’s Tacare Model

Sarah Graves is the coordinator for the Nelson Institute’s Environmental Observation and Informatics MS program, which is rooted in the disciplines of environmental conservation, remote sensing and GIS, and informatics.