“The story usually starts with carbon.”

This is what students learn in Tim Lindstrom Environmental Studies 126 class — a legendary course taught until 2017 by the legendary Cathy Middlecamp, who took it over from the legendary Cal DeWitt in 2013. To learn about carbon, students play the “carbon cycle game,” a dice game created by Kata Dosa — like Lindstrom, one of Middlecamp’s former grad students. But where to start when it comes to one’s own carbon cycle? “Breakfast,” says Middlecamp.

If the story usually starts with carbon, and carbon starts with breakfast, then this story starts with a bowl of plain Cheerios topped with sliced bananas and pears.

Middlecamp looks up from her cereal, taking note of Lindstrom’s outfit of the day. “You have the Alaska look,” she cajoles. In his green-gray full-zip fleece and yellow cap, complete with a large, black headset, Lindstrom does rather look like he could be piloting an Alaskan sea plane. “It’s just stamped on for all eternity now,” he shrugs.

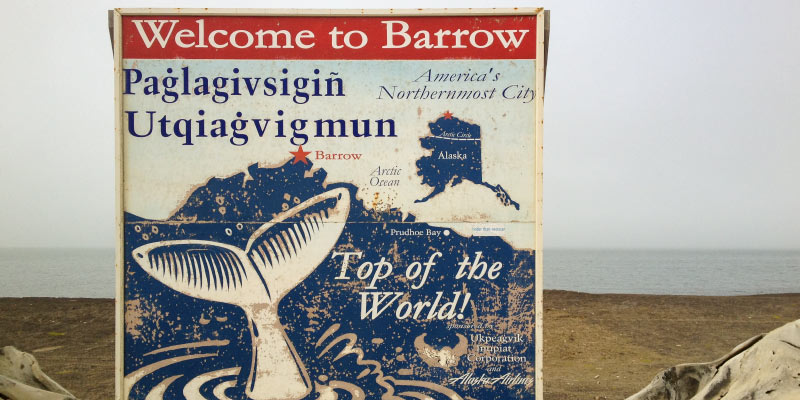

The student-becomes-the-colleague duo are referring to Utqiaġvik (oot-kee-AWG-vihk), also known as Barrow, a town of just under 5,000 on Alaska’s north slope. Lindstrom and Middlecamp have spent several summers there teaching a pre-college STEM camp at Iḷisaġvik (ill-ee-SAWG-vihk) College, the only tribal college in the state. This summer was no different — they headed to Utqiaġvik to teach two weeklong camps, Arctic Perspectives in Climate Change and Sustainability for high schoolers and The Science of the Invisible for middle schoolers. In late July, they packed their bags and flew from Madison to Minneapolis to Anchorage, where they hopped an Alaska Air jet to the Utqiaġvik airport (home of the town’s only paved road … the runway). The next leg of the journey was an even smaller plane to an even smaller town: Point Hope (population 674), which sits seven feet above sea level and a mere 150 miles from Russia.

At least … that’s how it was supposed to happen. But things don’t go according to plan during a pandemic, and they certainly don’t go according to plan when your destination is a remote corner of an enormous state.

Plan C … and D, E, F

From Anchorage, there’s one flight a day to Utqiaġvik. “During the summer, clouds often are quite low, fog is thick, and if it’s thick enough, planes won’t land,” Lindstrom regales. You can imagine where this part of the story is going — as their two-hour flight descends into Utqiaġvik, the runway in sight, “the plane just pulls up and starts going back up into the sky,” Lindstrom says. Middlecamp sets down her cereal bowl to model the flight path with her hands — down, down, down, pause, up, up, up.

“When that happens, they fly to Fairbanks, they refuel, and then they fly back down to Anchorage,” Lindstrom explains. “You basically are treated to a six-hour round trip flight where you wind up the exact same place that you left, never having gotten off the plane.”

But as Lindstrom said, this sort of thing happens often. It’s why their itinerary had them arriving in Utqiaġvik several days before the camp starts. They were rebooked for a Monday departure … same story. “Down, down, down, down, down; up, up, up, up; turn around, refuel, go back,” Middlecamp gestures again with a smile.

Back in Anchorage, they were offered a Wednesday rebook, but with the camp already under way — all students and the three other instructors having made it safely and on time — Lindstrom and Middlecamp called an audible and did what they could through Zoom. “At the tribal college in Barrow,” Cathy says, “You don’t need a plan B — you need a plan C.”

On Friday, they landed back in Madison. Not 24 hours later, they were both sick. “Our parting gift was a nice dose of COVID,” Lindstrom says as Cathy laughs. The two shrug off their harrowing adventure like seasoned pros. “You just roll with the punches,” Lindstrom says nonchalantly. “The folks who live and work up there, they just have a different way of doing things. Things happen a little more slowly than we in the lower 48 are comfortable with.”

“And this is not our first rodeo,” Middlecamp adds. It would have been her fourth summer teaching at Iḷisaġvik College; Lindstrom’s third. “Why is somebody from Wisconsin going all the way up to teach in Utqiaġvik, when you could have people a lot closer doing this?” Middlecamp suggests. “One thing leads to another,” she says. “There’s no short version of it … but I’ll try.”

One Thing Leads to Another

Middlecamp, a chemist by degree, has been a member of the American Chemical Society since 1976. That’s how she met Larry Duffy, a chemistry professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The two also work together on Science Education for New Civic Engagements and Responsibility — or SENCER — a national curriculum reform program. (“Teaching as if people in the planet mattered,” Middlecamp quips.) After helping Duffy with a grant proposal, he thanked her by inviting her to teach a summer camp at Iḷisaġvik College.

“I was enthralled, entranced, taken by the students, the tribal college, everything,” Middlecamp recalls. While there, she met one of Duffy’s students, Linda Nicholas-Figueroa. Middlecamp went on to become one of Nicholas-Figueroa’s PhD advisors, and Nicholas-Figueroa went on to become Iḷisaġvik’s only science faculty member — a post she holds today.

“And Tim, how did I enlist you to come back with me?” Middlecamp asks. “I was just the fortunate beneficiary of being your grad student!” he responds. “And what Tim’s not saying,” Middlecamp interjects, “is he’s a really good teacher. He and I taught in Environmental Studies 126 together for more years than I can count.”

Environmental Studies 126: Principles of Environmental Science is a core class for the Nelson undergraduate major, taught in a large lecture hall in a large building on a large campus in a large city. Lindstrom and Middlecamp’s summer class, which focuses on largely the same concepts, is taught in a small classroom with a window that looks out onto icebergs floating in the Arctic Ocean. It might seem like it’d be hard to translate the UW course to Iḷisaġvik, but it’s not — not if the place is the teacher.

Place-Based

The concept of place-based education has been around since — well, forever — but the term wasn’t coined until the 1990s. The idea is simple: learn using what’s around you. It’s a method that Middlecamp incorporated into ENVIR ST 126 when she took over after Cal DeWitt’s retirement in 2013. “The Nelson Institute doesn’t have any dedicated lab space with a stockroom, beakers, test tubes, microscopes or anything else,” she explains. “The campus was going to have to be my laboratory.” Middlecamp — with the help of Lindstrom, Dosa, Travis Blomberg, and Tom Bryan — turned 126 into a fully place-based course. “How’s that expression go,” Middlecamp asks, “necessity is the mother of invention? The same was true up at Iḷisaġvik College.”

In ENVIR ST 126, students visit the unions and residence halls to learn about food and waste. At Iḷisaġvik, they use the Arctic’s beaches and washed-up trash to learn about pollution. Both classes learn about energy and local infrastructure: in Madison at the Charter Street Heating & Cooling Plant; and in Utqiaġvik at the Barrow Utilities and Electrical Cooperative, Inc.

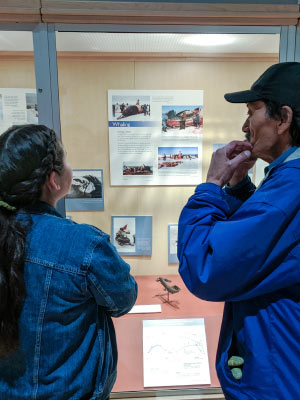

In Utqiaġvik, Lindstrom and Middlecamp also take their students to the tundra, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) research stations, and the Iñupiat Heritage Center, which they often visit with local elders who have been invited to speak at the camps. Interacting with the elders gives students a firsthand look into their communities have changed in just one lifetime. “[The elders] can speak to things like how the sea ice has changed over the years,” Lindstrom says. “There are all these differentiations between ‘young ice’ and ‘old ice,’ and there’s more young ice than there used to be, and that affects their ability to hunt.”

For Lindstrom, working with the Iñupiat elders left a lasting impression. “That was my first experience really being able to integrate the science that we were doing with traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous perspectives. I’ve tried to integrate that more into my own teaching here in Madison,” he says acknowledging that the UW campus sits onancestral Ho-Chunk land. “For me, that began in Barrow — or at least being woken up to the fact that science is one way of interpreting and explaining what’s going on, but it’s complemented with traditional ecological knowledge.”

Full (Arctic) Circle

Neither Lindstrom nor Middlecamp underplay the reciprocal nature of teaching at Iḷisaġvik College. For them, the lessons learned and friendships earned are well worth the occasional COVID-19–laden travel nightmare. “I had a lot to learn,” Middlecamp says of her first trip. “By the time I came back several times, I started understanding how food got in and out, how water got around, how energy was extracted from the ground, how the ocean was to be respected.”

Though Utqiaġvik is largely devoid of roads, Lindstrom and Middlecamp have paved a unique two-way street. “A three-way street,” Middlecamp corrects. “We learned from them, they learned from us, and they learned from each other,” she says. “Being able to learn from the students is probably one of the more gratifying aspects,” Lindstrom adds.

One of Middlecamp’s most gratifying moments is hearing students ask, “Are you going to come back?” “An awful lot of people drop in and drop out,” she says. “In other words, they check a box that they’ve been up there. It’s the people who go back that can make the difference. And there’s a group of us who are willing to go back and go back, and I think that’s important.”

So … are they going back? “I’d be really surprised if Tim and I and the rest of our Alaskan co-conspirators didn’t do this again,” Middlecamp teases. Lindstrom agrees — but adds a condition for their next visit.

“I want to see a polar bear,” he says, matter of fact. “I’m mildly disappointed that we haven’t seen one in the three weeks I’ve been up there.” “That’s because Tim runs faster than me,” Middlecamp jokes with a warm smile. “The bear would get me, and Tim would get away.”