Science Hall is a building that bares its soul, says Daniel Einstein, historic and cultural resources manager at UW–Madison and graduate of the Nelson Institute. “If one assumes a metaphor of the human body, we can see the skeletal structure, we can see the circulatory system, we can see the respiration occurring,” he elaborates. Science Hall’s innards aren’t hidden by drop ceilings or modern paneling; looking up, one can see its steel skeleton and patchworked piping, updated and repaired bit-by-bit over the years.

If Science Hall bares its soul, so, too, does it bare its history. On a historic tour of the building, Einstein is ripe with metaphors. From floor scratches to mismatched paint, the building is, as Einstein explains, a palimpsest. A palimpsest is an early form of writing material — say an animal hide or a tablet — that would be used and reused, often resulting in old writings appearing faintly behind new ones. In other words, something where both the past and present are visible in the same space. If you pay attention, you can glimpse into Science Hall’s history everywhere you look.

This month, the University of Wisconsin–Madison is kicking off a yearlong celebration of its 175th birthday. The Nelson Institute is proud to have been a part of that history for 53 years (and counting!), so to participate in the celebration, we decided to pay homage to Science Hall, the building that’s been our home since day one — and that’s been an icon on the UW campus since it was built. Come along for the journey as we examine Science Hall’s history by looking at its present.

Oh, Oh, Oh, I’m on Fire

The Science Hall that all living alumni know is actually Science Hall 2.0. The original building opened in 1877 — 29 years after the university was established, 28 years after the first classes met, and 26 years after the first campus building, North Hall, opened. But the original Science Hall was only around for seven years. “Then what happened? It burned, and in that fire, a lot of important research material and libraries were lost,” Einstein explains. Since Science Hall housed nearly every scientific department on campus, university leadership was eager to replace it … but with a less flammable option. In 1887, the new Science Hall opened in the footprint of the original. To this day, Science Hall remains the only university building to have been completely lost to a fire.

Frames of Steel

When the new Science Hall opened, it made history. In their quest for a fireproof structure, the building’s engineers opted for a relatively new technology: structural steel. In fact, Science Hall is the oldest, still-standing building to have used steel as its primary structural material. So when Einstein talks about seeing the building’s skeletal structure, he’s talking about one that’s almost entirely made of steel (plus a little bit of iron for good measure). In the building’s attic, some of these joints are on full display. Because steel was so new, the tools to properly cut and shape it didn’t exist yet. “They would get these large steel beams to the work site, and if they needed to shorten it,” Einstein says, “they would drill through the steel and then bend it until it broke.”

Hit a Wall

Like its iconic neighbor, the Red Gym, Science Hall was built in a Romanesque revival style. The two buildings share a castle-like exterior, high ceilings and arched doorways, and an extensive use of terracotta brick throughout. Many UW alumni are familiar with the brick walls of Science Hall’s upper floors, as they’ve long been used by graduating seniors to leave their mark — literally — on the university. As you climb the stairs from the first floor to the fourth floor, you’ll notice a switch from brightly painted brick to raw, exposed brick walls. This is one of Einstein’s palimpsests: “When the building was first constructed, there was no paint on the walls,” Einstein says. “It was all clay tile terracotta in natural form, which is to say, dark.”

Walking on Broken Glass

“I think one of the most delightful features of the building is something that a lot of people don’t necessarily notice,” Einstein says, pointing to the original stained-glass window above the main entrance. “Unfortunately, it’s falling apart. If you look at it closely, you can see that it’s bowing.” For more than a decade, Einstein has been leading the charge to get a conservation effort going for the window, but so far, the only solution has been to case the window in plexiglass so that if (or “when,” Einstein warns) the original glass breaks, it’ll be caught in the plexiglass and won’t shatter to the ground.

1-800-SCI-HALL

If you’ve walked through the front doors of Science Hall, you’ve likely walked right past a palimpsest. Just inside, to the left of the front doors at the bottom of the stairs, is a mint green rectangle that stands out from the rest of the cream-colored wall. “It’s about two feet tall, about 12 inches wide,” Einstein points out. “Can anybody think of what may have caused that layering of paint?” It was a payphone. At some pre-payphone point, the entryway walls must have all been painted mint green. But when it came time to repaint, rather than remove the payphone to paint behind it, the new color was painted around it, leaving the ghost of an old technology when the payphone was ultimately removed.

Floor Fossils

One of Science Hall’s original tenants was what we know today as the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum. Home of impressive collections, including a Boaz mastodon skeleton, the museum resided on the third floor of the south wing until it moved into Weeks Hall in 1981. The former museum space is now a student lounge and offices for the Nelson Institute’s Center for Culture, History, and Environment, but look down at the hardwood floor and you’ll see the faded, scratched-up outlines of where the museum’s collections once stood.

We Who Remain

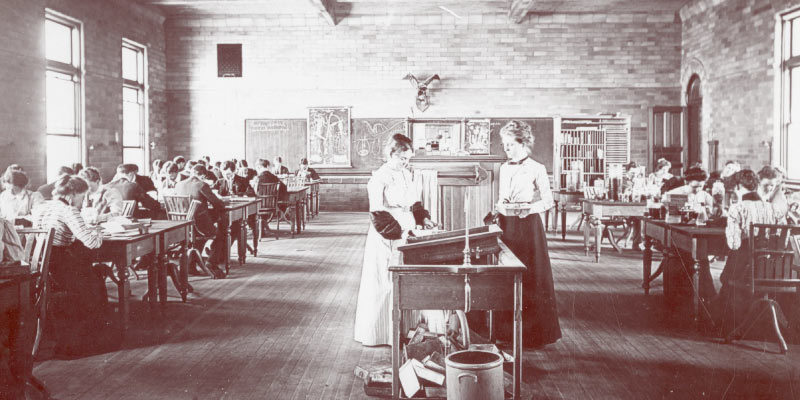

“This is where it all started,” says Einstein. When then-president John Bascom and the Board of Regents requested funding for the first Science Hall, they did so to accommodate the rapidly growing student population. “A Hall of natural science,” the 1874 report stated. “This, as it seems to us, is just now the one great desideratum of the University.” Once it was built (and then rebuilt), Science Hall became home to almost every science-based department. “Many, many departments had their beginnings in this building,” Einstein explains. “As they expanded, they got their own buildings” — and many of those buildings were each larger than the whole of Science Hall. Engineering moved out in 1901, followed by botany in 1910 (to Birge Hall), physics in 1917 (to Sterling Hall), and the medical school in 1928. The next exodus started a few decades later: meteorology went to the Atmospheric, Oceanic, and Space Sciences Building in 1968; geology moved into Weeks Hall in 1974 (followed by the Geology Museum in 1981), and lastly, the Department of Chican@ and Latin@ Studies left for Ingraham Hall in 1995. So, who’s left? The Nelson Institute and the Department of Geography (and the UW Cartography Lab) are the only two who remain, surely leaving their own palimpsests on the building for future generations to come.