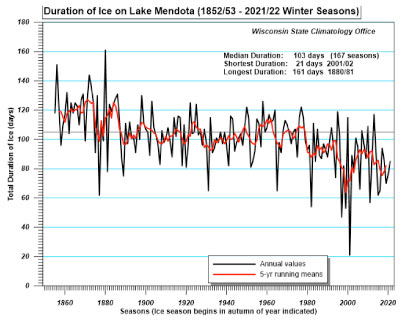

“Is Lake Mendoza frozen yet?” Believe it or not, that’s a common wintertime question from alumni seeking reports from their alma mater (particularly alumni who have migrated to warmer climates). Thanks to the Wisconsin State Climatology Office, that data are easily found … and has been for the past 171 years. Dating back to 1852, you can see when the lake froze and when it opened. From 1855–1865, the average duration of ice cover was 119 days. For the past 10 years, it’s been only 83 days. The efforts of the State Climatology Office don’t just give us a look at how Lake Mendota has changed, but a larger picture of climate change in the state of Wisconsin.

A joint effort between the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences and the Nelson Institute’s Center for Climatic Research, the State Climatology Office’s mission is to provide data-led analysis and evidence of climate change and share that information with Wisconsinites, from individuals to government agencies. The office also serves as the official records holder for the state’s climate records.

The earliest version of the State Climatology Office dates back to the late 1800s. From 1870–90, volunteer observers in the U.S. Army Signal Service recorded weather observations across the state. With the creation of the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) in 1891 those duties transferred, and the state of Wisconsin started collecting and publishing data through the Wisconsin Section of the USWB. That first office ran out of Milwaukee until 1948 when the Wisconsin Section was parceled into regional centers, which is when Madison’s location came into the picture. By 1956, nearly each state had its own state climatologist and staff under the USWB, which in 1970, was renamed to today’s National Weather Service (NWS).

Budget constrictions led to the termination of the NWS’s state climatologist program in 1974, but the state of Wisconsin continued to fund its position: partially from 1974–76, then fully — with joint appointments in UW–Madison’s Department of Meteorology and UW–Extension — for the next couple of decades.

In the 1990s, Madison’s State Climatology Office underwent a period of massive transition. The office — and the position of state climatologist – went from being fully funded to having no funds at all. But that didn’t stop the work. For the past couple decades, the State Climatology Office — housed in the Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences Building — has had the duo of Young and Hopkins at its helm: John Young, who served as director from 2002–22, and Ed Hopkins, assistant state climatologist since 2003.

The Icemen Recordeth

Young came to the UW in 1966, joining the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (AOS) as a professor — now emeritus — of meteorology. An expert in global climate processes, including El Niño events, Young found himself fielding numerous press inquiries and attending conferences following the 1997–98 El Niño that caused droughts and flooding that affected the globe. Seeing the importance of UW expertise going beyond the boundaries of campus, Young began to push for increased funding to the State Climatology Office.

Young came to the UW in 1966, joining the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (AOS) as a professor — now emeritus — of meteorology. An expert in global climate processes, including El Niño events, Young found himself fielding numerous press inquiries and attending conferences following the 1997–98 El Niño that caused droughts and flooding that affected the globe. Seeing the importance of UW expertise going beyond the boundaries of campus, Young began to push for increased funding to the State Climatology Office.

“When I started my second term as AOS department chair, I convinced Dean Phillip Certain to provide funds to keep the office open,” Young recalls. “I partly succeeded — the part-time office manager, Lyle Anderson, was funded. But there were no funds to support a state climatologist position, so Certain named me the unpaid director.”

Having a director, albeit an unpaid one, helped the State Climatology Office be recognized in the American Association of State Climatologists, where Hopkins, Young, and other UW–based experts have now become regular contributing members.

“Surprisingly, my role as pro bono director lasted nearly 20 years,” Young says. “During this period, we established connections with Wisconsin client groups such as agriculture and climate data applications.” The position has allowed Young to continue his public outreach (“in my ‘meteorologist wearing a climatology hat,’ ” he jokes), including hosting the 2018 Wisconsin Climate Services Summit Meeting that connected 50 academic and governmental organizations.

As Young describes, despite shifting funds in the UW Division of Extension and state governmental reluctance to support climate change issues, the State Climatology Office succeeded in positioning itself as a trusted expert — “Particularly,” he says, “through the efforts of my associate Ed Hopkins”.

As assistant state climatologist, Hopkins supports the day-to-day operations of the office — from responding to questions to generating weather and climate data tables to maintaining the office’s website. Hopkins is also the one carrying on the nearly 200-year tradition of ice-cover recording.

The first recorder’s identity is unknown; the earliest named recording is from 1935 when meteorologist Eric Miller published a pamphlet of the information. From the 1980s to 2016, office manager Lyle Anderson kept the books, and Hopkins took over for him upon his retirement. You might think that the method to recording when the lakes freeze and open would have changed over the past 171 years … but you’d be wrong. The dates are still called by eye. “We’ve tried to maintain that same mentality of how it looked to people in 1850,” Anderson told the Wisconsin State Journal.

“This chronology that can be traced back to the 1850s is arguably one of the longest continuous lake-ice chronologies in North America,” Hopkins says. “I hope that the State Climatology Office continues this set of phenological observations that help reflect our changing climate.”

A Good Forecast

Although the work of the State Climatology Office is robust, it has largely been unfunded by the state, making Young and Hopkins’ contributions a labor of love. But that’s all about to change, thanks to new funding from the 2022 Agriculture Appropriations Bill.

In December 2022, UW–Madison announced its partnership on a new initiative to support rural communities as one of three nationwide universities who comprise the new Institute for Rural Partnerships. A total of $28 million from the Agriculture Appropriations Bill was divided between the UW, Auburn University, and the University of Vermont; the UW’s portion totaling $9.3 million. Of that, $1.3 million has been earmarked for the Nelson Institute’s Center for Climatic Research (CCR) to help revitalize and expand the State Climatology Office.

“We’re excited to be able to revitalize the state climatology office,” says Michael Notaro, CCR’s director. “It will allow that office to serve communities across the state in a more interactive way and by being more in touch with folks. That’s the key.”

The grant will run for four years; in other words, the State Climatology Office will have to continue its fight for long-term support. For now, Young and Hopkins will continue to lead by example, working tirelessly to demonstrate the office’s value to the state of Wisconsin.

“Now that funding for the office has at last been found,” Young adds, “we hope that our efforts will be recognized as a foundation for the achievements of the future State Climatology Office, involving enhanced efforts on climate variability and change impacting the citizens of Wisconsin.”

The funding has also led to a fully supported position of state climatologist — the same role that Young has been championing for 20-plus years. Young looks forward to the new dimensions of applied climate science that this position will open up. An open search is underway to fill the position and serving in the interim is the Nelson Institute’s own Steve Vavrus.

Vavrus has been with the Nelson Institute since 1990, and he currently serves as a CCR senior scientist and the codirector of the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts. He’s also a dual Badger, having earned his master’s and PhD in meteorology from UW–Madison.

“John and Ed have put forth heroic efforts to keep the office going for all these years,” Vavrus says of the State Climatology Office’s legacy. “How many people can claim such service for more than two decades?”