Coverage, fish, cube, duration. What connects these four words? That’s right, ice! And when it comes to ice duration and ice coverage, few places have better records than the Wisconsin State Climatology Office. Maintained by assistant state climatologist Ed Hopkins — known among friends and fans as the “Ice Man” — records of freezing and thawing on Lake Mendota date back to 1852. (That’s just three years younger than the university itself.) What can these records tell us about Wisconsin’s changing climate? A recent data analysis from Hopkins offers good news for migratory birds and bad news for ice fishers: less ice, more water.

For starters, it’s taking longer for Lake Mendota to freeze over. The UW student experience may have looked entirely different in 1886 than 1986, but Badgers of both centuries got to enjoy icy activities before heading home for break. Compared to 1971, Lake Mendota now freezes over about 15 days later, and this century, the majority of “ice-on” dates have been in January.

There have also been seasons where vastly fluctuating temperatures have caused multiple freezes, like the 2024–25 winter. “Lake Mendota has been unusually fickle this winter,” says state climatologist Steve Vavrus. “[We saw] a brief freeze-over on Christmas Day that melted off a couple days later, followed by a long stretch with open water. Despite the really cold weather since the start of January, the recent sustained winds kept ice from reforming lake-wide until January 7.” It’s no wonder the ice is confused this year: it reached 50 degrees on January 17 … and four days later, plummeted to a low of -13.

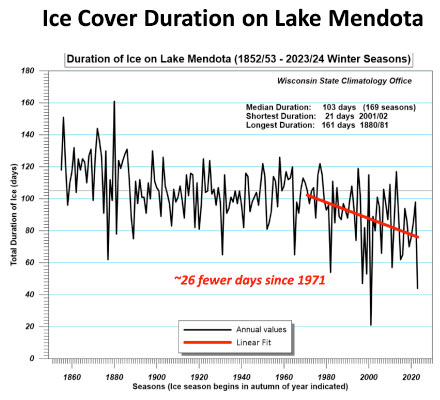

According to Vavrus, the best trend indicator is duration of coverage, however, rather than ice-on dates. “There have been a lot fewer days with ice cover on Lake Mendota in recent decades as the climate warms,” he summarizes. Since the new millennium, the average duration of ice coverage is 82 days; in the 1800s, it was 114. The longest duration of ice occurred in 1880–81: Mendota froze just before Thanksgiving and didn’t thaw until May 3. Through 1999, the lake would typically stay frozen until April. But since 2000, 57 percent of “ice-off” dates have jumped to March. All told, that’s about 10 fewer days of ice coverage today than there were in 1971.

When you look at the increase in annual temperatures across the Madison area, the loss of ice makes sense: it’s 2.3 degrees warmer than it was in 1971. If that trend continues, Badgers 50 years from now might never get to lace up their skates on the frozen shores of the Terrace. Ice activities aren’t the only winter pastimes at risk. Just last year, northern Wisconsin’s historic Birkebeiner ski race had to shorten its course due to lack of snow for the first time.

Fortunately, groups like the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI) are meeting these challenges head on. In fact, its tourism and recreation working group has laid out a series of actionable steps that the state can take to both mitigate the effects of and adapt to our warming world. Offers Vavrus, who also serves as the organization’s codirector, “Proactive approaches like these are increasingly necessary as Wisconsin adjusts to a ‘new normal.”