Like many other Indigenous groups, the Maya don’t view nature as a resource to take from, but as a collection of subjects to build reciprocal relationships with. A cornerstone of Maya culture is the relationship they have with sacred Melipona bees and the forests that these stingless bees live in. Unfortunately, in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, these forests are being cut down in order to develop plantations that are fumigated with toxic pesticides. These farming practices that have spread across Yucatán kill bees, contaminate water, and encroach upon Maya land — all threatening Maya culture.

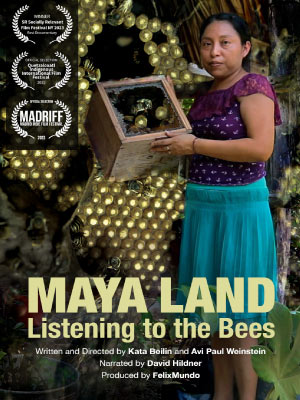

The struggle of the Maya against this model of development is depicted in the documentary film Maya Land: Listening to the Bees, which was released last fall and codirected by Kata Beilin and Avi Paul Weinstein. Beilin earned her PhD as a literary scholar, but soon transitioned into the field of environmental humanities. “I was always very interested in what was happening around me, and advocating for the environment felt very important,” she says. Today, she is a professor in UW–Madison’s Department of Spanish and Portuguese and an affiliate of the Nelson Institute’s Center for Culture, History and Environment.

Drawn to the relationships between man, culture, and nature, Beilin began to research the protests of Maya beekeepers against genetically engineered soy farming. While working on a paper with Sainath Suryanarayanan about this issue, the idea for a film emerged. “An image can say more than thousands of words,” Beilin explains, “and we thought that these issues could be of interest to a wider public.” The pair had already recorded 40 interviews with Maya people and others involved in the conflict, giving them a great starting point for the rest of the film.

Maya Land: Listening to the Bees “explores the pre-colonial and ongoing relationship between Maya people and their environment, in particular the milpa agricultural system (and its main crop, maize), sacred sinkholes (called cenotes), and sacred stingless bees, the Melipona,” according to Beilin and Weinstein. The film also examines how these cultural cornerstones are being threatened by genetically engineered soy plantations, which have quickly spread across Mexico in the 21st century due to their economic benefits. These monocrop plantations introduce pesticides which poison the bees, leach dangerous chemicals into the soil, and contaminate water pooled in cenotes and the underground basin. “Maya people are fighting against this to keep their culture alive,” Beilin explains. She hopes the film will draw attention to issues the Maya face.

The film — which can be viewed for free online— has been returned to the Maya people at a screening at the Mayan Intercultural University of Quintana Roo in José María Morelos. Since its release, Maya Land has been screened at universities, conferences, and film festivals in the US, Mexico, Uruguay, Spain, and Germany. This spring, Beilin’s film won the documentary feature category of the SR Socially Relevant™ Film Festival in New York. Above all else, Beilin takes the most pride in how her film is being used. She reports that the film is being used in “Maya beekeeping seminars, classes, and as an outreach method to search for more allies for the Maya.”

While the Maya have won the legal battle against genetically engineered soy planting (thanks to alliances with scientists, lawyers, and international activists), Beilin shares that the crop is still being planted illegally in Yucatán and illegal pesticides are being used on other crop plantations. Maya beekeepers continue their fight in the newly formed Kaabnalo‘on Alliance, which connects 83 Mayan beekeeping communities that advocate for environmental action on behalf of the bees. “In Maya, Kaabnalo‘on means ‘we are beekeeping people,’” Beilin says, “and they believe that in places where bees are healthy, people and other creatures are healthy as well.”

The fight against genetically modified soy plantations is only a small chapter in a long history of resisting colonization, Beilin claims. Last spring, she was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to further research the history of Maya resistance and is working on publishing a book about it. “Maya resistance can take different forms,” says Beilin. “Sometimes it’s violent, sometimes it’s silent, sometimes it’s a legal battle or artistic protests.” Because this resistance always returns, she is titling her book The Return of the Mayan Moment, which will combine the historical context of Maya resistance with the struggles they face in the 21st century.

Beilin hopes that through her book and film, Maya culture will inspire people to think about the relationships they have with forests, water, all living creatures, and land. She particularly emphasizes the reciprocity, respect, and identification with the territory that all foster Maya spirituality. “I think the Maya are wiser in the way that they structure their dialogue with nature,” Beilin shares.