Growing up in northeastern Massachusetts, the frequent winter snowstorms (and days off from school that accompanied them) piqued Jon Martin’s interest as a kid. This childhood fascination turned into a professional interest in the systems behind visible weather patterns as Martin pursued an education in atmospheric and oceanic sciences. During his time at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Martin’s interest in cyclones (which are the behind-the-scenes weather systems that bring along the winter weather that he was most enthralled by as a kid) grew. He also developed a new interest in the way weather systems interact with and are impacted by climate change. Now a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and affiliate of the Nelson Institute, Martin’s recent research connected him with the Center for Climatic Research.

Q: What is your current research focus?

A: I’ve been linking weather systems and their operation to how they alter — and are altered by — the climate system. Everybody’s looking at this problem as the Holy Grail because some fraction of the public is still skeptical about whether or not our climate is changing to begin with. We may be able to convince them by showing them how changes in the weather are related to the changing climate, so we need to understand how climate change is imposing itself on changes in the weather. Wisconsin in particular is positioned to make great contributions compared to our peer universities around the country. There’s no better assemblage of scholars with knowledge about both weather systems and the climate system, and this group has proven to be adept at working together in a collaborative way.

Q: Is there a specific project you’re working on right now?

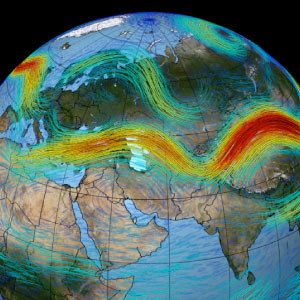

A: Right now, I’m working on understanding the interannual variability of the Pacific Jet stream, which is the portion of the jet stream that has fairly important impacts on the weather in North America. The physical mechanisms that underlie changes to the complexion of the North Pacific Jet might be altered in a changing climate. Knowing how these physical changes are wrought in the Pacific could also be applicable to segments of the jet stream in different parts of the world.

Q: What have your findings been so far?

A: In the northern hemisphere, there’s a polar jet in the middle/higher latitudes, and a subtropical jet around 20 degrees north of the equator. There’s evidence that both jets are becoming systematically wavier in the past six decades, but we don’t know if that’s a result of the changing climate or whether it exacerbates other phenomena that might be brought along with a changing climate. We’ve recently developed a simple, robust method for measuring how wavy the jet is – I think our method is better than prior competitors – so I feel like we are in a better position as a community to determine if the jet actually is getting wavier.

Q: How might a wavier jet impact the weather we see?

A: The waves in the jet are the physical features that produce weather systems. I haven’t proven it yet, but it stands to reason that there are strong connections between a wavier jet and more episodic extremes in the weather. If you have higher amplitude waves in the middle latitudes during the wintertime, for instance, there might be a greater frequency of both warm and cold spells – quite different from past patterns.

Q: What do you wish other people knew about the field of science?

A: If you make a hypothesis and you’re wrong, you still stand to learn something. When I first arrived in Wisconsin, I started looking at occluded cyclones, which are cyclones that have reached the late stage of their lifecycle. Occluded cyclones take on a whole different kind of thermodynamic structure than other cyclones and are accompanied by heavy snow production in wintertime. When I started investigating occluded cyclones, my initial hypothesis about their connection to heavy snowfall was entirely wrong, but the truth that the error revealed left me with a brand-new insight about the way the whole cyclone system worked. That’s the great thing about science; nobody ever loses, things just may not come out the way you thought they would.

Q: What is your favorite part of your job?

A: When it comes to weather and climate, everyone has an opinion, and everyone will tell a story about the weather or climate in their life; it makes an impact on all of us. As a meteorologist, anybody you talk to will have at least a slight interest in what you’re talking about, and they’ll have something to tell you in return. It’s insightful and really neat.

Q: Are you teaching any classes this upcoming semester?

A: One class I teach in the fall is the senior undergraduate/first-year graduate student course on weather systems at the middle latitudes. I have a very captive and eager audience in that class, and I try to match their enthusiasm with the same energy. In the spring, I teach Introduction to Weather and Climate, and I love doing that too. I’m thrilled to introduce people to the elegance of science and its bulletproof nature. You can’t just make things up, pretend they’re true, and make a career out of such presentation, because you’ll get stopped in your tracks. I try to teach these students that the constant criticism and skepticism from other scientists is not corrosive, but beneficial to sharpening our understanding of nature and becoming a better scientist.

Although Martin is nearing the end of his career, he encourages undergraduate students to reach out to be connected with other experts in the atmospheric and oceanic sciences field.