“You need to talk to Tracey Holloway,” Nelson Institute Dean Paul Robbins told Jeff Rudd. Rudd, a Nelson alumnus, had recently reconnected with his alma mater and was attending an event as a newly minted Board of Visitors member. He had heard of Holloway — she’s rather an A-lister in the science community — but he hadn’t met her yet. “Paul asked me to talk to you about converting the energy analysis and policy certificate program into a master’s program,” Rudd said as he approached Holloway, who was stepping into a leadership role in the program. “Bad idea,” she replied. “Okay. Tell me why.” They talked for the next two hours.

That was 10 years ago. Since then, downtown Madison has seen the installation of Free Little Libraries with solar-powered phone charging stations. A PhD student attended two COP conferences after publishing a policy analysis on the Paris Agreement. A group of students published their capstone work in an esteemed journal. All of this happened because of a flourishing certificate program — which couldn’t have happened without Rudd’s support. Though if it were up to Rudd, this story wouldn’t be about him at all.

Looking at Rudd’s history, one might be surprised to learn about his connection to an environmental studies institute. But therein lies the interdisciplinary magic. “I think interdisciplinarity is a cornerstone of helping people really overcome some of the limitations that they may impose on themselves,” he says. Rudd’s story is devoid of self-imposed limitations, perhaps because he’s long embraced uncertainty.

As an undergraduate student at Virginia Tech, Rudd double-majored in biology and philosophy. “Philosophy intrigued me because it was hard and it asked a lot of questions,” he reflects. “It required me to write and communicate about issues that a lot of people care about but are reluctant to talk about.” The link between biology and philosophy, Rudd found, was uncertainty. Can we ever know the nature of knowledge? The meaning of life? What things can’t scientific inquiry prove? Why? Rudd found comfort in uncertainty, allowing it to lead the way.

With his interdisciplinary wheels turning, Rudd leapt to his next stepping stone: law school at Washington and Lee University. Digging up his roots in the outdoors, he began to explore a path in environmental law policy. “I quickly learned that most of the people were there to become lawyers, and I adapted in that direction.” Adapt he did, and after graduating, he was a practicing attorney for a decade. He was good, but it was hard. “You become a little bit numb. The criminal justice system is a hard place,” he reflects. “I always wanted to reconnect with that connection to the outdoors that I had.”

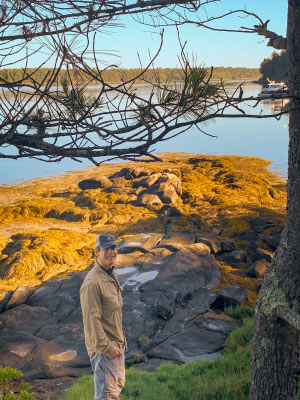

Although Rudd grew up mere miles from the Pentagon, his childhood was largely spent outdoors. He remembers backpacking trips to the iconic Blue Ridge Mountains, which lie among the state’s 3.7 million acres of public lands. From his career in the legal industry, he knew the complexities of creating policy, and he grew curious about public lands like the ones from his youth. Of the lower 48 states, Montana has the third highest acreage of public lands, so that’s where Rudd went to learn more.

He started his PhD work at the University of Montana, doing ecological and environmental policy fieldwork. He loved the work — and he really loved the location — but his interdisciplinary background felt mismatched, especially if he wanted to teach one day. His advisors guided him to a major research university where he could craft a truly interdisciplinary PhD committee: UW–Madison’s Nelson Institute and its environment and resources program.

There he linked up with his advisor: Clark Miller, an associate professor who now leads Arizona State University’s Center for Energy and Society. “What do you know about nanotechnology?” Miller asked him at their first meeting. “Really small stuff?” Rudd joked. He walked out of the meeting with a three-year research position with the UW’s Nanoscale Science and Engineering Center. “I walked outside, and I literally laughed because that was completely unexpected,” he remembers. From the vast public lands of Montana, he began to study the environmental implications of nanotechnology. “My dissertation dealt with the progression of the nanoscale, the National Nanotechnology Initiative, and then the Nanotechnology Research and Development Act,” he explains. “It was a bird’s eye view into risk and uncertainty.”

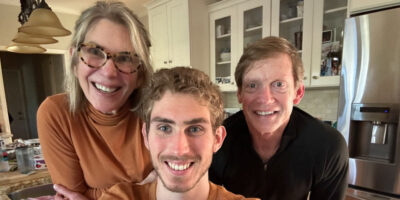

While completing his research, Rudd discovered another area of interest, which carried perhaps more risk and uncertainty than any field he’d explored before: the stock market. Trading and investing are what occupy his days now, though it’s less of a passion project. “Do I like it?” he muses. “I like being able to do it, to help me help others and help my family be in a position to feel that they can do the same. That’s what I like.” What he loves is uplifting the next generation of interdisciplinary scholars, and he found that outlet back in the Nelson Institute and its energy analysis and policy (EAP) program.

Launched in 1980, EAP is one of the world’s oldest graduate energy programs. It began as a 40-credit certificate option for master’s students in the environment and resources (then “land resources”) program, but over the years, it synthesized into a smaller credit-hour program to allow for virtually any UW–Madison graduate student to participate. Enrollment started to drop again in the 2010s, but fortunately that’s when Rudd and Holloway, now the program’s director, connected. With his own diverse background, Rudd was able to help Holloway forge key relationships that helped expand the program’s connections. “She’s the reason it happened,” Rudd deflects. “She can say that it wouldn’t happen without me, but I don’t buy it. I just happened to be there.”

But “just” being there proved to be lucrative for the program, as Rudd’s vast experience brought not only new connections, but new ways of thinking about the opportunities for academia and the private sector to unite. “One of the fundamental issues was how [to] improve the student experience,” Rudd says. “As the EAP program evolved, we were already thinking about how do we bring in people from the outside, from the private sector to provide feedback … that might lead to redesigning the curriculum or enhancing the student experience.” That’s what led to the current structure of EAP’s capstone course. In it, small, interdisciplinary student teams are paired with private sector clients to work on real-world projects: like creating energy kiosks at Free Little Libraries for the City of Madison or detailing the potential of renewable gas for the Minnesota Department of Commerce. “Tracey and I, with input from Paul Wilson and Greg Nemet, viewed [the capstone] as the foundation for redesigning and expanding the EAP model,” Rudd says. “Relationship building was, and is, key to EAP’s success.”

Since then, enrollment in the program has more than doubled, becoming far and away the most popular graduate certificate on campus. And as far as Rudd’s concerned, the program is a shining example of just how impactful interdisciplinary work can be. “It can be the leading edge for what this university wants to do — but doesn’t realize it yet — in terms of interdisciplinary work,” he says. “You want to break down silos, you want to look for an example of how to connect with the private sector, amplify your students’ learning experience? Look at EAP.” Or, perhaps, just look to Rudd.