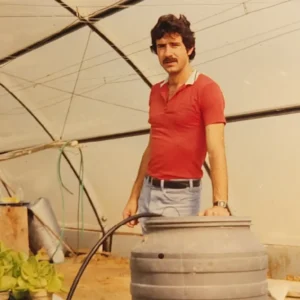

How Alberto Vargas turned interdisciplinary interests into a career-defining strength.

How Alberto Vargas turned interdisciplinary interests into a career-defining strength.

The post The Transdisciplinarian appeared first on The Commons.

Read the full article at: https://nelson.wisc.edu/the-commons/alberto-vargas-the-transdisciplinarian/