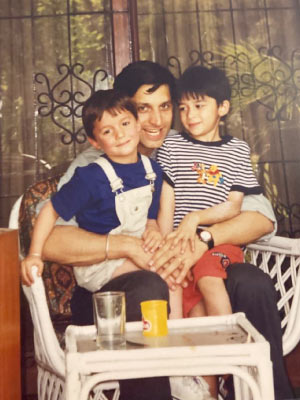

Surrounded by mangoes, Nyal Mueenuddin remembers his childhood as fun, sweet, and sticky. His family owned a mango farm along the Indus River in Pakistan’s southern province of Punjab, and it was here that his connection with the environment began, and where a piece of him will always live. “Mangoes were a big part of my childhood,” he said. “I lost my first tooth biting into one.”

Mueenuddin’s parents both worked for the United Nations and international non-governmental organizations, which took Mueenuddin around the world as he grew older. After bouncing around from place to place and completing high school along the way, Mueenuddin traded mangoes for cheese curds and applied to attend the University of Wisconsin–Madison where he was granted a Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) fellowship for South Asian studies through the U.S. Department of Education.

In college, Mueenuddin’s interests blossomed into environmental studies, communication, photography, political science, and, of course, South Asian studies. “I really loved going to a big university like UW–Madison because I could scroll through hundreds of different courses and find really niche topics that I was interested in,” Mueenuddin said.

One of the classes that especially stood out to him while completing his degree was History, Geography, and Environmental Studies 460: American Environmental History with Nelson Institute Professor Emeritus Bill Cronon. “That was probably the best class I took at UW–Madison,” Mueenuddin said. “[Cronon] inspired me a lot, not just because of the subject matter, but by his way of teaching. He was a storyteller.”

As Mueenuddin continued through college, he kept Cronon’s creative storytelling in mind and employed it wherever possible, including his capstone course with Professor Alfonso Morales. The course focused on food deserts, food rights, incarceration, and the environment, and when Mueenuddin pitched the idea of creating a documentary film for the class instead of writing a final paper, Morales was all for it. At the end of the course, Mueenuddin turned in a 20-minute film about the revolving prison door in Madison and the efforts of a Black farmer as he helped people stay out of prison by learning how to farm.

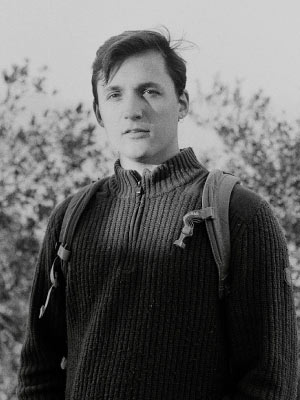

After graduating from UW–Madison, Mueenuddin began working as a junior researcher with a team studying humpback whales in Madagascar. At that time, he thought he wanted to pursue a career in marine science, but as he worked, noticed that there was a need for photos and videos of what the researchers were doing, which launched him back into the storytelling side of science. “Being involved with the Nelson Institute was essential in building a foundation of knowledge, interest, curiosity, and a feeling that I was capable of doing things a little bit outside of the box,” Mueenuddin said.

He then moved back to Pakistan and began working with the World Wildlife Foundation doing photojournalism around the country. After two years of that, Mueenuddin was put in touch with the BBC, which wanted his help with an episode of Planet Earth III that focused on the Indus river dolphin. “They sent a team out, we shot, and it was super successful,” Mueenuddin said. “After that, I decided that I wanted to be with other filmmakers and that I had more to learn about the craft of filmmaking.”

Mueenuddin enrolled in a year-long master’s program at the University of the West of England in the United Kingdom, regarded as the capital for natural history filmmaking. After completing that program, Mueenuddin set off to create a documentary about the aftermath of Pakistan’s devastating 2022 floods that displaced 30 million people and had a third of the country underwater. He traveled 3,000 kilometers down the Indus River where most of the flooding happened and interviewed 40 people about their stories and memories of living along the river and how it has changed since the flooding.

Mueenuddin is now screening the film in Pakistan and plans to start a documentary production company based in Islamabad that will tell climate, environment, wildlife, migration, and human stories. “It’s a big step, but I feel like all of the experiences I’ve had up until now have prepared me for it, including being at the UW,” he said.

For students looking to follow in his footsteps, Mueenuddin encourages them to just go for it and jump in however they can. “Filmmaking is fun,” he said, “And if you can start off by experimenting with things you think are interesting, it helps stoke a fire in you that ultimately makes the whole future feel more reassuring.”