It’s the circle of life – which is something Department of Entomology faculty member and U.S. Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) research entomologist Shawn Steffan knows all too well. Through his decades of education and research, Steffan finds the “who eats whom” question fascinating. “I did my PhD at Washington State University on fear ecology and predator biodiversity,” Steffan said. “It was community-scale ecology that relates to agriculture, but also just to natural systems and food webs.”

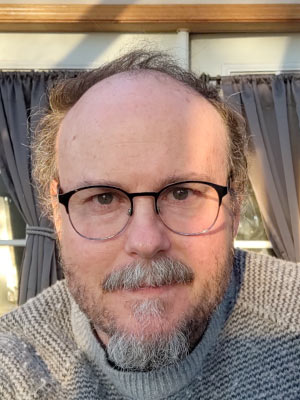

Here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Steffan spends his time running the Steffan Lab, which is part of the USDA–ARS Vegetable Crops Research Unit as well as the Dept. of Entomology. He conducts a multi-faceted research program while co-teaching classes and guest lecturing. His research centers on trophic ecology, as he uses a variety of molecular methods to explore food-webs and how they affect plant protection. As the US Cranberry Entomologist, his work focuses on cranberry crop preservation, pollination, and bee-microbe symbioses. Steffan answers some of our most burning questions about bee health and ways to protect cranberries using sustainable methods.

Your recent work is looking at cranberries. Why is Wisconsin the cranberry capital of the world?

Wisconsin has these natural environments that are already very conducive to cranberry production. The cranberries that we grow in cultivated beds are actually native plants, only a generation or two from wild populations. Water management is a huge part of growing cranberries … and Wisconsin has lots of water. Almost every grower has their own reservoir so they can flood and maintain their beds. Another reason is growers need a lot of space to gather their water reservoir, and Wisconsin land (in the central part of the State) is often relatively inexpensive. Also, the soils and surface waters tend to be acidic in the cranberry growing regions, which is how cranberries like it. The combination of vast marshland areas, abundance of water, and acidic soils helped Wisconsin become ‘cranberry central.’ For a long time, Wisconsin was not the number-one cranberry producing state. Now we grow more cranberries than all other US states combined and dominate global production.

How has your cranberry research influenced Wisconsin’s crops?

We created a novel tool — a bio-insecticide — that uses native nematodes that we effectively tracked in the central peatlands of Wisconsin. We trapped them by putting out insect hosts, almost like live trapping a bear or wolf, and screened a bunch of nematode species for their virulence. We found two that are highly virulent to insects, and particularly to the top pests of cranberries. Every insect we screened them against, the nematodes were able to kill. These two species are super effective at worming their way through soil and killing cranberry pests.

The other part of my cranberry research is a pheromone-based mating disruption program. What this does is effectively fog the cranberry canopy with the sex pheromones of insect pests, which prevents the male moths from finding females. Fertilization, obviously, is required to make a viable egg. If we can intercede and prevent the males from finding the females, fertilization doesn’t happen, and we can preempt the existence of that caterpillar. It’s an elegant and pesticide-free way of hugely reducing the pest pressures in cranberries. This work is ongoing because we’re still looking at ideal carriers and timings for applications in Wisconsin cranberries.

How can students get involved with your research?

Typically, students see my website and that nucleates a conversation, and from there, I can tell them what future directions I’m looking at. Then they’re either interested in that direction or not. I try to facilitate the development of a research question with my students, which allows them to have real ownership in the ideas, questions, and goals. try not to spoon-feed the students but help them along by providing resources, “crumbs” along the path, and lots of discussions. I have them articulate their research question in their own words, which hopefully lights a fire in their belly.

How can the general public help with your research?

Consider bee microbial communities. We are reframing the whole concept of this two-way symbiosis and making the case that it’s really a three-way symbiosis between bees, microbes, and plants. So, if you want to conserve bees, you need to also consider these microbial communities that are vital to the effective fermentation and processing of their food, their nectar-pollen provision. So, just making the case that to help the bees, you also have to help conserve their microbes. Spraying less fungicide on flowering plants is one way we’ve shown to help preserve certain bee-associated microbes.

Now for the important questions. Which do you prefer: canned cranberry sauce or homemade?

Oh, homemade! You can adorn it with so many other things. I like adding ginger or some kind of citrus. It’s definitely a staple for Thanksgiving.