What do you get when you combine the immediacy of the climate crisis with the nuances of public policymaking?

You don’t have to answer that, but Morgan Edwards could with her ongoing research at the Climate Action Lab, a University of Wisconsin–Madison research lab that focuses on energy and climate policy led by Edwards. An assistant professor of public affairs at the La Follette School of Public Affairs, Edwards also has affiliations with the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment and a variety of other centers on campus.

With a BS in environmental science and economics, SM in technology and policy, and PhD in engineering systems, Edwards is more than capable of diving into every aspect of energy and climate change, especially when it comes to problems where social and technical factors both play an important role. In doing so, she combines large datasets, community knowledge, and systems modeling to assess the multidimensional impacts of human energy use and help design plans to move towards a more just and sustainable energy and climate future.

With a BS in environmental science and economics, SM in technology and policy, and PhD in engineering systems, Edwards is more than capable of diving into every aspect of energy and climate change, especially when it comes to problems where social and technical factors both play an important role. In doing so, she combines large datasets, community knowledge, and systems modeling to assess the multidimensional impacts of human energy use and help design plans to move towards a more just and sustainable energy and climate future.

I sat down with Edwards to discuss her research and teaching and what she has learned over the past decade about how to make climate policy work.

What classes do you teach?

I currently teach two courses. The first is Cost-Benefit Analysis, which is an advanced graduate, project-based course. It’s really fun because we get clients working at all different levels of policy who have questions about the costs and benefits of environmental policies. The students work directly with these clients to develop a rigorous policy analysis that may be used to inform real policy decisions. This semester, our students will be looking at everything from the benefits of electrifying the vehicle fleet here in Madison to options for increasing the reliability of refrigeration for vaccine storage in Sub-Saharan Africa. I also teach Evidence-Based Policy Making as part of our undergraduate Certificate in Public Policy. The goal of this course is for students to be able to be critical consumers of the different forms of evidence that we use in public policy by studying cases where evidence was used well or poorly in the policy process. We also talk a lot about inequities in how evidence is produced and communicated and pressing problems like mis- and dis-information.

What’s your favorite thing about teaching/working with students?

Oh, there’s so many things! I really enjoy working with students to develop open-ended projects. A lot of the work they do, especially as undergraduates, has a right and wrong answer. In the real world, the most interesting and important problems are a lot more complicated. I think having the kinds of classes that are more subjective, where there’s not just one right answer, really prepares students for their future jobs and life beyond the university. That’s a really fun aspect of teaching.

What’s an example of an open-ended project?

One example is public policies to electrify our energy use. That’s a big part of the incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act. We have a billion machines that rely on fossil fuels in our homes — things like furnaces, stoves, and cars — and I’ve worked with students in my classes and in the Climate Action Lab to understand how we might electrify households in ways that have economic and environmental benefits. Take air source heat pumps, for example. Sometimes having a heat pump can reduce your energy bills, but other times it can raise them. So, we’re trying to find new ways to calculate these impacts and figure out how we can use public policies to bridge that gap, especially for low-income households, and to develop transparent tools for individuals looking to make the switch.

Speaking of your research, you lead the Climate Action Lab at UW–Madison. What have you been up to there?

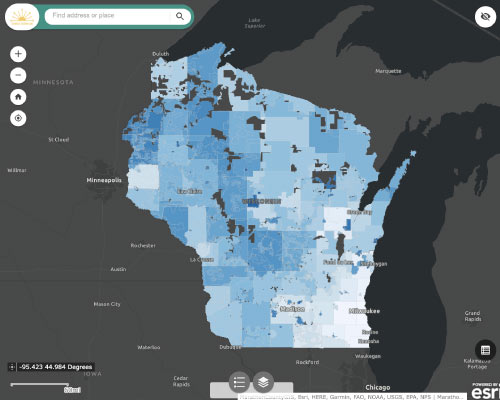

It’s an exciting time to be working in energy and climate policy! We focus on modeling and tracking the effects of climate actions from local to global scales. One of our big projects is working to create better ways to capture the details of energy technologies in the models we use for setting long-term climate policy targets. A big part of that work is thinking about how to model technologies like carbon dioxide removal. Many of them are in the early development stages today, and whether they can scale up quickly in the future is really uncertain. We’re working on ways to better model new technologies, even when we don’t know a lot about them or the role they might play in climate action.

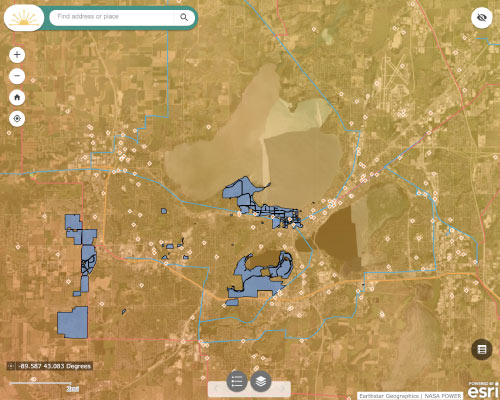

Another big project focuses on planning equitable fossil fuel phaseout in buildings. Currently we burn a lot of natural gas to provide heat in our homes, especially in colder climates like here in the Midwest. A lot of this work is driven by the needs of community partners. There are important questions about how to transition in a coordinated way so that we don’t leave folks behind. We also work to understand how to best balance long-term climate solutions like electrification with shorter-term solutions like repairing or replacing leaky gas pipelines in cities.

How did you get into this climate crisis/energy responsiveness side of policymaking research?

How did you get into this climate crisis/energy responsiveness side of policymaking research?

I always knew I wanted to work on addressing the climate crisis. When I started college as an undergraduate, I thought I wanted to study climate policy, so I majored in economics and was studying political science. My thinking at the time was we know the science of climate change, so now we need to focus on solutions and implementation.

Then, as I continued in my undergraduate degree, I began to realize there are lots of big unanswered scientific questions as well, especially about the effects of energy technologies and how the technical and policy sides interact. So, I switched, and I studied environmental science, did my PhD in engineering systems, and then went back to public policy as a President’s Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Maryland. Now, I’m happy to be affiliated with the Nelson Institute, where I don’t have to divide myself between science and policy but can do both at the same time.

What do you find most interesting about your field of expertise?

Climate policy is one of those areas where we imagine people are more polarized than they actually are. A lot of surveys on climate change actually show that most Americans believe climate change is happening, they believe humans are the cause, and they think that public policies should do something about it. At the La Follette School, we spend a lot of time talking with state and local policymakers and with communities throughout the state. Last year, we held a series of town halls leading up to the election. People were much more concerned about climate change and interested in discussing solutions than you might believe from listening to the news.

Sometimes I think it also comes down to linking climate change with people’s values. One value that many people can get behind is innovation and access to clean energy technologies. These bring a lot of local benefits beyond just climate change mitigation. They make our air cleaner and are often easier and more comfortable to use. So, there are a lot of situations where we can get broad agreement on some of the key solutions that we need to address the climate crisis, but part of the way that we do that is we link it to other things that people care about, not just climate change.

What are some common misconceptions about climate policy?

That the costs of addressing the climate crisis are very expensive. The costs of not acting are far, far greater than the cost of doing something about it. We’re also seeing that for a lot of climate solutions are getting more and more affordable, and in some cases, cheaper than conventional fossil fuel technologies.

Any advice for students who are interested in climate policy?

This is a very solutions-oriented field, so I would suggest finding a question that’s really interesting to you and try to come in with an open mind about the way that you might answer that question. You might find that the tools you need are ones that you’re not familiar with, so don’t be afraid to go out and learn new things. We need all hands on deck to solve the climate crisis!