For Sara Hotchkiss, a professor of botany and an associate of the Nelson Institute’s Center for Climatic Research, Center for Culture, History, and Environment, and Center for Ecology and the Environment, thinking outside of the box and giving students the space to develop their skills and explore their passions have been the pedestals of her career. With a cross-curricular background, she’s found ideal academic homes within the Botany Department and the interdisciplinary Nelson Institute, where she feels supported in her endeavors to ask hard questions and follow the science, even if it leads outside of her core academic discipline.

Hotchkiss, who now studies ecology, vegetation and climate history, ecosystem responses to climate change, disturbance and landscape dynamics, and paleoecology, is interdisciplinary in every sense. In fact, she began her academic career as a cellist.

“I was a cellist, lucky enough to finish high school at Interlochen Arts Academy, and then I went to Oberlin College because I could do both music and science there, in an atmosphere that emphasized social justice. I did a biology major and many of the requirements for an ethnomusicology major,” Hotchkiss said. “I kept myself broad through college, I took plenty of humanities, participated in the Oberlin Student Cooperative Association, played in the gamelan orchestra and the steel drum band. My biology professors probably thought I was majoring in steel drums.”

While the steel drum band was just for fun, she did meet the leader of a Yale cell biology lab at one of their concerts in Connecticut. After graduation, Hotchkiss joined the lab and spent a year studying skin cancer in the Department of Dermatology.

“It was a blast, the people were amazing and I learned a lot about cell biology, but I just felt the questions closing in around me. I was studying melanoma and throwing away radioactive plastic every day, and I felt uncomfortable that wealthy people could afford to treat advanced melanoma and other people couldn’t. I knew my perspective was limited, but something wasn’t right for me,” Hotchkiss said.

So, the next year, she moved to Minnesota and worked on sustainable agriculture in Dave Andow’s insect ecology lab for a few months before spending spring working in a greenhouse and summer mapping a permanent plot in old-growth forest in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan with Margaret Bryan Davis. That fall, she began graduate school having chosen ecology as her core discipline.

“While I chose ecology, it was a very broad ecology, evolution, and behavior graduate program at the University of Minnesota, and ultimately I added an interdisciplinary minor in Quaternary studies,” said Hotchkiss, who enjoyed her initial project in population genetics, but said she again felt the questions closing in around her. Unsure of her true calling, she found herself thinking back to that plot of forest in the Upper Peninsula.

“That old-growth forest taught me something. I was lured by perspective, unanswerably complex questions about ecological communities, things that have legacies and trajectories longer than human life spans, and the folks in Margaret Davis’s research group had a refreshing sense of humility about their work,” Hotchkiss said. “In retrospect, I realized that many of my strongest memories from childhood were of poking around the woods.”

Realizing that her true interests lie in complex, interdisciplinary questions that have impacts and implications beyond her own lifetime, Hotchkiss began studying ecological responses to climate change through the lens of paleoecology, the study of ecosystem history, and Margaret Bryan Davis became her PhD advisor.

“It was the early ‘90s and although it wasn’t yet prominent in the news, scientists were very concerned about climate change. I could see that a lot of people were working on that,” Hotchkiss said. “I chose to study the responses of ecosystems to climate because I didn’t see as many people thinking very deeply about that yet. I decided to take the slower road, toward depth, because I wanted to do something with my life that few other people were likely to do, that used my particular strengths, and that would be of use beyond my lifetime, whenever enough people began to realize how much we had altered both climate and ecosystems. I was lucky to be in a lab where that kind of long-trajectory thinking was supported. I didn’t expect that we would be discussing climate change as a political issue while I was still in my 50s!”

After completing her PhD, Hotchkiss and her partner Basil Tikoff moved to Wisconsin, where she was welcomed by then director John Kutzbach into the Center for Climatic Research while she did a postdoc in ecosystem ecology with Peter Vitousek at Stanford. In 2000 she was offered a tenure-track position in the department of Botany, where she is now a full professor. There her students study community and ecosystem ecology, paleoecology, and Quaternary paleoclimatology, but everyone is encouraged to think outside of their academic boxes and given the space to find a project that is novel and will have lasting implications.

“I’m really glad that I have landed professionally in one of the universities that has the longest experience with interdisciplinary research and education because I think that’s essential for our most important environmental problems,” Hotchkiss said. “I encourage a broad range of projects in my research group. I am not a top-down advisor. We are diverse in terms of humanity and in terms of projects. Our lab is really a research collaboration, and the students finish their degrees knowing they can design, fund, and accomplish research that takes a broad perspective on science and builds on their own strengths.”

Hotchkiss shared that students who join her lab have generally worked outside of the sciences in varied roles. For example, she has had students who were in publishing, sculpture, community activism, museum work, government and non-profit conservation management, and more. She values this diversity, as it brings new perspectives to the research and she feels that it strengthens all of the students’ professional development as well as her own experience.

“I love being able to work with people who are not only scientists; that’s healthy for me. And I really benefit from the long history of interdisciplinary at this university. Interdisciplinary research and education have developed here over more than 50 years, and people understand its value,” Hotchkiss said of the Nelson Institute. “This is really good for the students, but it’s also great for the world because the most challenging kinds of problems the world faces are not contained within disciplines.”

While the work within the Hotchkiss Lab is varied, Hotchkiss has maintained continuous research and long-term collaborations in the Hawaiian Islands with Oliver Chadwick and Peter Vitousek and in the Western Great Lakes region with Beth Lynch and Randy Calcote. She seeks perspective on ecosystem responses to changes in climate and cultures using deep study of natural history and two main approaches: reconstructing several histories in a landscape, so that she can perceive local differences in responses of ecosystems to changing climate, and mining ecosystem history for examples of rare events, like extreme multi-decadal droughts and sudden state-shifts in ecosystems.

“Sara is among the Institute’s most selfless and thoughtful leaders,” said Nelson Institute Dean, Paul Robbins. “Under her watch, we have launched a new Center for Ecology and Environment, explored a new program in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and put stronger foundations under our Environment and Resources graduate program.”

In fact, Hotchkiss was recently named a Vilas Associate by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The Vilas Associate Competition “recognizes new and on-going research of the highest quality and significance” and awards recipients salary support and research funding over two fiscal years. Hotchkiss plans to utilize this support to build a tool that will make counting microfossils much faster.

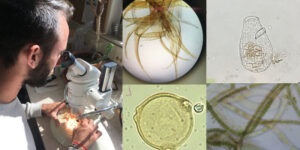

“Paleoecology relies on people counting things, which is incredibly slow work. It requires a tremendous amount of expertise. It takes a year to get any good at counting pollen, and you have to spend that year and then go back and recount your samples,” said Hotchkiss. “You need to be able to recognize a huge variety of microfossils. For example, a one-centimeter cube of mud from a lake bottom can have many thousands of pollen grains in it, and that’s a lot of information about vegetation. There’s not only pollen in there. There are little bits of insects, there are fungal spores, algae and zooplankton, chemicals from breakdown of pigments, DNA, dust, amoebae, all kinds of things. We want to know what they all are. A lot of people go into this field because they love looking at the beautiful tiny things and enumerating them and I like that too, but I really am interested in gaining perspective on ecosystems. If you do it all by hand you can get a lot of information about a spot where some stuff accumulated at some time in the past, but you won’t be able to study many places or slices of time in one human career. So the Vilas is about developing a tool that we can use to ask different kinds of questions about landscapes and history, questions that require amounts of data that would take generations of expert humans to produce.”

Essentially, they are looking to develop a tool that will use rapid imaging microscopy and image classification tuned to particular microscopic components of ecosystems. Hotchkiss plans to utilize existing technology and develop artificial intelligence-based image classification in collaboration with Alex Wiedenhoeft and Prabu Ravindran for three different purposes. One is to count phytoliths, which will help Hotchkiss to learn what plants used to grow in dry places, especially in the Hawaiian Islands where ecosystem restoration projects need local information. Another purpose is to analyze charcoal, which will help her understand fire histories with greater spatial resolution than current methods allow. This is an area of research in which undergraduates in the Hotchkiss Lab have a leading role. Third, Hotchkiss and her lab will investigate the history and distribution of microplastics in the environment.

“I’m really glad that I have landed professionally in one of the universities that has the longest experience with interdisciplinary research and education because I think that’s essential for our most important environmental problems,” Hotchkiss said.

Hotchkiss is excited to get started on this work and for her students to take a lead in helping her develop these three areas of the Vilas Award project. She hopes that through this experience, her students will have the space and support needed to maximize their expertise while exploring new ways of thinking and developing new methods of discovery.

“In academia, we are rewarded for expertise and productivity. So, we like to define a box and then maximize our expertise in that area. We really need that approach–for example, I have my box, I know pollen morphology and plant ecology well. But that focus comes sometimes at the cost of perspective and flexibility. I think our students really need to develop their perspective and flexibility, along with expertise,” Hotchkiss said. “It’s important to ask those humbling questions that are beyond anyone’s current expertise, and the Nelson Institute encourages that. Society has really benefited over time by setting aside universities where people can follow questions beyond the limits of our understanding. We need some people thinking deeply and seeking perspective without primarily chasing short-term rewards; when we support that, collectively we all benefit. I give students that space for a few years, and they blossom. Having seen that happen, I really can’t do it any other way.”