While attending the Rhode Island School of Design for her undergraduate degree, Liz Anna Kozik became very aware of the fact that she was a Midwesterner on the East Coast. “I felt weird surrounded by people from either coast. Everyone came from cities with long histories, and I came from Chicago nowhere suburbia,” Kozik said. “But one special thing that I did have growing up was prairie.”

Kozik lived next to the Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Illinois, and while living on the East Coast, she drew from her past environmental experiences at the Arboretum and the Illinois Prairie Path to inspire her art. Centered around prairie aesthetics, her work aims to communicate environmental issues as efficiently as possible, combining intriguing illustrations to pull viewers in and concise text.

After graduating, Kozik returned to the Midwest to work as a product designer, but soon felt the pull to return to her work in an academic setting. She then enrolled at UW–Madison and started her MFA at the School of Human Ecology in the Design Studies program, combining art and environmental studies that she developed her education into a PhD.

“I picked the Nelson Institute because interdisciplinarity was the point, and the program gave me the freedom to build my own committee across different disciplines and work with scientists and humanities scholars. That flexibility couldn’t really happen anywhere else,” Kozik said.

Her PhD looked at prairie restoration through historical and ecological lenses with the goal of obtaining a grounded experience that balanced both the humanities and science sides. Kozik wanted to make sure that her work didn’t fall into the traps of focusing on one side over the other. Take, for example, invasive species. “There’s lots of interesting writings about invasive species, and some humanities scholars who argue that invasive species doesn’t exist as a category, just a cultural idea. On the other hand, scientists face a very real problem where a problematic species is taking over a habitat and that it needs to be managed,” Kozik explained.

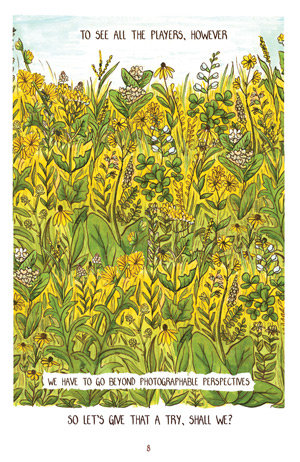

As an intermodal scholar, Kozik’s dissertation was produced through the work of comics — fully illustrated works that are specifically geared towards accessible language. “Or at the very least, using the least amount of words to talk about very complicated subjects,” Kozik said, pointing that the goal of her work was to make information more available to more people, and not just other scholars.

On top of that, Kozik uses a specific style to draw people into her art: “My work is very aesthetically pleasing, and that is a very intentional choice. It’s kind of like carnivorous plants that smell like dead animals to attract insects into them. I make something very pretty so it’s compelling, and in the end, you end up reading complicated things you wouldn’t read otherwise.”

Even as a humanities scholar, Kozik appreciated the opportunity to work with scientists in the field, one being Ellen Damschen, a professor of Integrative Biology whose research focuses on prairie and savannah biomes. “I was invited into her lab as a full member and attended meetings and interacted with scientists. I didn’t feel like I had to apologize for my background but was welcomed for the diversity of perspectives that I brought to the table,” she said.

Now graduated, Kozik works as a research coordinator for the Rethinking Lawns project at the Chicago Botanic Garden. Her position combines her experience as a science communicator and researcher as her team investigates native alternatives to lawns with the goal of increasing biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and stormwater infiltration.

Looking back, Kozik advises others looking to complete a PhD to “build a committee that supports your goals while still being academically challenging.” For her, that was accomplished through MacArthur genius and world-famous comic artist, Lynda Barry, who sat on Kozik’s committee. “One of the benefits of being a Nelson student meant that I got to have Lynda Barry on my committee, who treated comics just as much an academic discipline as the other disciplines I was working within,” Kozik said. “That was a wonderful opportunity, and I couldn’t have made the work without that.”