Fill in the blank: It takes courage to ___________.

Fill in the blank: It takes courage to ___________.

What comes to mind? Maybe you see firefighters or police officers or soldiers. Perhaps you think of the courage to get out of bed in the morning or to ask someone out on a date. The courage to ask for what you need; the courage to fight for the ones you love.

But what about the courage required to simply exist on this planet that is being, and has long been, ravaged by climate change? How do you build resilience needed to make change? And can you?

Just as we have researchers studying solar energy and scientists analyzing air quality data, there are researchers and scientists who are investigating these very questions. The emotional aspect to environmentalism is a growing field, and quickly. It was only 14 years ago that two researchers from the Lewis & Clark Graduate School of Education and Counseling published the first journal article detailing the impacts of climate change on the mind. Since then, the connection between the climate crisis and mental health has appeared in everything from academic journals to the New York Times.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison are offering a way to manage these ecological emotions and build resilience in the midst of change: through developing climate courage. But what does that look like in practice? For some, it’s easy to turn anxiety about the climate crisis into action. But for an increasing number of environmentalists across generations, those feelings are dwelling and metastasizing — from something as small as a bad mood or an “off day” to panic attacks or paralyzing depression — making it really hard to show up. These feelings are real; you can name them.

So, let’s start there.

Ecological Emotions

Ecological Emotions

Negative feelings about the environment — or climate distress — typically fall into one of two categories: eco-anxiety or climate despair. The American Psychological Association defines eco-anxiety as “a chronic fear of environmental doom. Climate despair — or sometimes climate grief — refers to a state of hopelessness. Following a parallel structure to how your run-of-the-mill anxiety and depression manifest, eco-anxiety is associated with heightened feelings (think: racing thoughts, panic attacks, chronic worry), whereas people with climate despair experience decreased drive: low mood, loss of interest in things, feeling of futility.

Sound familiar? You’re not alone. Research shows that more than 50 percent of young people worldwide have experienced emotions like sadness, anxiety, and hopelessness about climate change. In Wisconsin, 60 percent of residents have expressed some level of concern about global warming. A study across Europe showed that more than 42 percent of respondents felt very or extremely worried about climate change.

“As environmentalists, it is important to remember that our wounds exist because we feel pain on behalf of the Earth, on behalf of the species or the landscape we love,” says Dekila Chungyalpa, director of the Loka Initiative at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The Loka Initiative — a cross-campus interdisciplinary program housed within the UW’s Center for Healthy Minds — helps an array of faith leaders and Indigenous culture keepers to build capacity for personal, social, and ecological resilience in their respective communities. It was through defining those emotions — and discovering language for them — that Chungyalpa found her way into this work.”

It was the early 2000s, and she was the only woman of color, and Indigenous at that, to be a field director at the World Wildlife Fund. She’d just been promoted, becoming the organization’s youngest field director as well. On the surface, she’d “made it.” But she had consistent nightmares about what she was seeing in the field. “You could walk for half an hour in parts of the Mekong region and not hear a single bird,” she remembers. “It made me realize that the future was immensely bleak for humans and non-human beings and that the conservation work ahead of us was herculean, almost impossible, but we could not talk about how that made us feel” The psychological dissonance began affecting her sleep. Then she read a paper by Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht, who coined the term solastalgia. He defined it as the immense grief experienced by those who are deeply connected to nature and the land. “It was like something clicked inside of me,” Chungyalpa remembers. “Someone finally named what I was feeling.” Naming it allowed her to begin processing those emotions, setting her on a path to the work she does today.

So, where do you land? Eco-anxiety, climate despair … maybe a bit of both?

Have your answer? Good. Naming it is just the start. Now … let it all in.

Rewiring Your Brain

When you put a name to your feelings, you’re actually engaging in an awareness practice. This type of work goes by many names: meditation, mindfulness, contemplative practices, and so on. Though the details may differ, the result is the same: rewiring your brain.

“Awareness is a necessary ingredient for any kind of change to happen,” says Dr. Richard J. Davidson, founder and director of the Center for Healthy Minds and founder of Healthy Minds Innovations. “We need to be aware of what’s happening in our minds and bodies, so that we can understand how we are responding.”

“Awareness is a necessary ingredient for any kind of change to happen,” says Dr. Richard J. Davidson, founder and director of the Center for Healthy Minds and founder of Healthy Minds Innovations. “We need to be aware of what’s happening in our minds and bodies, so that we can understand how we are responding.”

Think of your brain like a series of giant networks. Each network comprises different regions, and each serves a unique function. For example, your central executive network directs your behavior and attention. (You see a dirty dish. You think, “that should go in the dishwasher.” You get up and put the dish in the dishwasher.) There’s also the default mode network, which is basically your autopilot mode. (Do you default to making mental lists? Reliving awkward conversations over and over again? Winning arguments with your in-laws that haven’t, and will likely never, happen?) These networks, among numerous others, are “constantly, dynamically in play,” Davidson says.

Mindfulness and meditation practices can change how those networks connect to each other and work together. “When we’re meditating with eco-anxiety, for example, we may not get rid of the eco-anxiety,” Davidson says, “and that’s not really the point.” The point is to change your perception of and relation to those feelings of anxiety. But all of that starts with naming your emotion — and then giving yourself permission to feel it. Over time, and with practice, your brain will learn that your ecoanxiety or climate despair isn’t all encompassing … even if it feels that way.

“It’s just like clouds in the sky,” Davidson illustrates. “The sky doesn’t change from the clouds. You can have storm clouds, but eventually it’ll change. When we say we ‘are anxious,’ [it’s like saying] the clouds are the sky. There are simple training techniques that allow us to pull them apart, and that’s the beginning of real change.” And that’s how emotional resilience becomes a skill.

By this point, you’ve named your ecological emotions, you’ve sat with them, and you’ve renegotiated your relationship to them. Big changes ahead: ready for the next step? Bring your awareness to the good stuff.

Take the Good with the Bad

Think back to where we started: how do we build our resilience — our climate courage — so that we can take action?

For Chungyalpa, there are three ingredients: joy, connection, and courage. These emotions, she says, are energizing, empowering, and activating. “Joy is absolutely necessary because it allows us to counter emotions that are more depressive, more nihilistic,” she explains. Davidson might refer to this as “gratitude,” or engaging in awareness practices to recognize the good in your life. “We have people that we love, people that take care of us, that we take care of,” he says. “Just recognizing this, bringing loved ones into your mind and your heart — it’s really amazing how accessible these kinds of virtuous emotions are.”

Among its benefits, Davidson offers practicing gratitude as a way to cope with overwhelm from news and other sources. For Chungyalpa, on the other hand, feeling joy and gratitude helps build connection — which goes hand-in-hand with building courage. Because, she points out “our first instinct when we experience joy is to turn around and share it with someone else.”

Admittedly, it can feel a little weird to allow yourself to revel in joy when there’s a constant stream of terrible news running like ticker tape in the back of your mind. Have you ever thought, “How can I possibly be happy when [insert latest headline here]?” Or maybe on an unseasonably warm and sunny early spring day, you think, “We don’t deserve to enjoy this right now.” That, reader, is guilt, and it’s standing in the way of your resilience.

Admittedly, it can feel a little weird to allow yourself to revel in joy when there’s a constant stream of terrible news running like ticker tape in the back of your mind. Have you ever thought, “How can I possibly be happy when [insert latest headline here]?” Or maybe on an unseasonably warm and sunny early spring day, you think, “We don’t deserve to enjoy this right now.” That, reader, is guilt, and it’s standing in the way of your resilience.

Chungyalpa defines guilt as having a wound that you either created yourself, or one that was created on your behalf, that you don’t know how to make amends for. Some of her recent research indicates that guilt is particularly paralyzing when it comes to dealing with eco-anxiety and climate distress. “It’s destructive to movement-building,” she says, “because what is essentially happening is that you’re centering your own emotions to such a point that you may not be able to show up for others the way you actually want to.” More to the point, ruminating on guilt keeps the focus on you, not the movement. “What kind of emotion can you activate that would make you counter that?” Chungyalpa asks. Courage! “Courage overrides your sense of guilt to actually just say, ‘I might be doing something that is not completely right, but I am showing up in the most open and authentic way I can.’ ”

Seeking out joy and gratitude — and letting go of guilt — can feel hard. Particularly when you’ve been caught in a cycle of thinking the clouds are the sky, if you recall that metaphor. “When we try something new and it’s uncomfortable, most of us don’t go back,” Chungyalpa says. But you tried, right? You flexed that muscle that’s been enjoying a rest day/week/month/year? That’s you exercising your courage.

“What we do know about courage is the more you exercise it, the more you gain it,” she explains. “The best part about courage is that you typically don’t exercise it just for yourself. Courage is an emotion that you often exercise on behalf of someone or something else.”

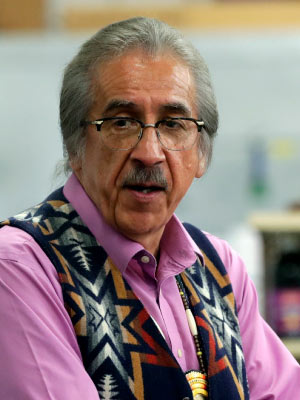

If there’s anyone who knows a thing or two about speaking up for others — human, animal, and landscape alike — it’s Gary Besaw.

Courage in Action

For Besaw, director of the Menominee Nation’s Department of Agriculture and Food Systems, climate courage doesn’t look like an awareness practice or gratitude journal. It’s tangible, lived, and rooted in tradition.

Besaw has spent this career in tribal legislature, holding the positions of tribal chairman, vice chairman, and secretary, as well as serving on the Wisconsin Legislature’s State-Tribal Relations Study Committee. He’s seen a lot — and he’s held a lot of responsibility. “As an Indigenous person, we’re the canary in the coal mine. We see things that, many times, decision makers … don’t see or experience,” he describes.

“You want to know where the white hair comes from?” he laughs. “It’s terrible when you … truly understand some of the implications of what could happen if we don’t step forward.”

As tribal chair, he held a responsibility to be the voice for his people, their land — and all its inhabitants. From a young age, Besaw learned the importance of connection between humans and our nonhuman relatives. “We’re told that we are the pitiful ones,” he recalls. “All these other animals, they can live without us. If humans disappeared, they’d have a field day. But if they disappeared?” he asks, rhetorically. It’s systems thinking, he says. All parts of the system have to work together, and in support of each other. “Don’t make decisions where you know that the deer, if he could speak and had a voice, he’d lift his hoof up and say, ‘Mr. Chairman, I’m gonna vote no.’ ”

This is what Chungyalpa and Davidson’s work is helping us all move towards: courage that is rooted in connection, not the self. It’s this type of courage that can build communities, build movements, and make change. And while the work of ecological emotions and climate courage is new for the lexicon of Western research and academia, it’s not new. In fact, it’s because of courage — the collective courage of the generations before us — that we’re able to have this conversation today. What about seven generations from now?

Look out your window, and picture that landscape in 100 years from now in the context of the current climate reality. What do you feel: are you scared? Anxious? Depressed? Chungyalpa had pointed to a specific feeling: nihilism. “‘Why does it matter? We’re all screwed anyway,” she defines. We learned that joy can be one counter to this, but Besaw offers another.

“It’s our responsibility,” he says. “I’m gonna be able to see my grandkids, God willing. I can bounce them on my knee … It’s your great-great-great-grandchildren that you’ll never see, so some people will go, ‘Phew, I don’t have to look them in the eyes. I don’t have to feel guilty [for not taking action.’ ” That’s an excuse people use, and I refuse to [put] the onus now on my great great grandkids.”

And Chungyalpa would agree. “One of the reasons why I talk about climate courage or environmental courage so much is to get us to switch from the mindset that ‘we need to be saved’ to one where ‘we are the protectors.’ ”

Fill in the blank: It takes courage to ___________.

What comes to mind now?

- It takes courage to accept responsibility for my actions.

- It takes courage to speak up for those who don’t have a voice.

- It takes courage to name and accept my emotions.

- It takes courage to protect the future.

When we started this journey, we asked not only how to build resilience in the face of the climate crisis, but also if we can. So … can we? On April 22, 1970, U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson gave a speech to commemorate the first Earth Day. He wondered the same thing. “Are we able to meet the challenge? Yes,” he said. “Are we willing? That is the unanswered question.”

Hear from Dekila Chungyalpa, Richard Davidson, Gary Besaw, and a host of other climate courage experts at the upcoming Earth Fest Forum: Climate Courage – Finding Resilience in the Midst of Change. This free, public event will take place on Wednesday, April 22, from 2–7 p.m. at UW–Madison’s Discovery Building. Presented in partnership with the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, the UW–Madison Office of Sustainability, and the Center for Healthy Minds, the Earth Fest Forum is a headliner event for UW–Madison’s larger Earth Fest 2025 celebration.

In addition to music and dance performances, art installations, and opportunities to build connections, the forum will host Chungyalpa, Davidson, and Christy Wilson-Mendenhall for a discussion on the “Psychology of Deep Resilience.” Then, Besaw and Chungyalpa will participate in a panel discussion called “Stories of Resilience,” also featuring climate/health expert Jonathan Patz, environmental activist John Francis, and Nelson Institute alumnus and staff member Christopher Kilgour.

Kira Adkins, a senior majoring in environmental studies and legal studies with a certificate in American Indian studies, was tapped to moderate the panel. “It’s a very interesting group of people that I’m really excited to speak to,” Adkins says. “I think they can all offer something that represents truly what intersectionality is in the environmental field.”

In preparing to lead the discussion, Adkins has already found some takeaways. She’s learned that climate courage is rooted in the idea that we — humans — are fragile and fundamentally connected to the environment. “The foundation of us doesn’t begin with us at all,” she explains. “We are being cared for, and we’re rich in abundance because of the fact that we are fragile. The trees are bigger than us, the water is bigger than us. We are at their pleasure, and at the same time, we need to take care of them.”

Find Courage at Earth Fest

Find Courage at Earth Fest

Earth Fest Forum: Climate Courage

Wednesday, April 23 | 2–7 p.m.

Learn more and register