For students in Environmental Studies 922: Historical and Cultural Methods in Environmental Research, research doesn’t take place in a lab or a library. Graduate students in this seminar use the land as their laboratory, investigating the visible and hidden ways that humans and their environment have changed over time. The three-credit seminar — colloquially called the “CHE methods class” — is a three-credit seminar required for the Center for Culture, History and Environment (CHE)’s graduate certificate.

For students in Environmental Studies 922: Historical and Cultural Methods in Environmental Research, research doesn’t take place in a lab or a library. Graduate students in this seminar use the land as their laboratory, investigating the visible and hidden ways that humans and their environment have changed over time. The three-credit seminar — colloquially called the “CHE methods class” — is a three-credit seminar required for the Center for Culture, History and Environment (CHE)’s graduate certificate.

This year, the class integrated another of the center’s offerings: CHE walks, or “mini place-based workshops,” as center director Will Brockliss explains. Led by CHE faculty associate Beatriz Botero, the walks brought students to Tewakącąk (Devil’s Lake) near the Wisconsin Dells and Indian Lake State Park in northwestern Dane County. There, students found inspiration for their class project, which required them to examine and reflect on the environmental and human history of the area.

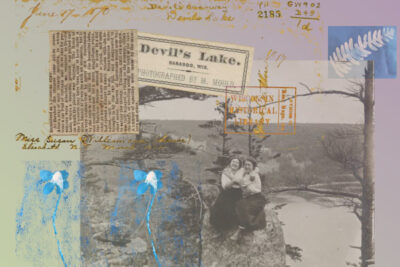

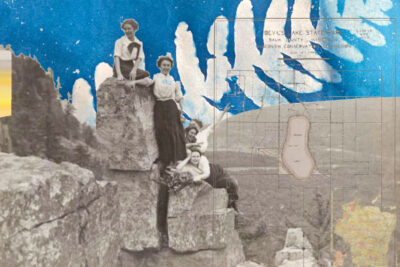

Dani Burke, a PhD candidate in design studies, took her inspiration from a guest lecture by Tomiko Jones, CHE faculty associate and assistant professor of photography. Burke created collages using analog, digital, and archival photography, as well as maps and other archival materials.

Dani Burke, a PhD candidate in design studies, took her inspiration from a guest lecture by Tomiko Jones, CHE faculty associate and assistant professor of photography. Burke created collages using analog, digital, and archival photography, as well as maps and other archival materials.

Artist statement:

With this project on Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake, I wanted to experiment with analog and digital photography, and to layer these images with archival material. These four collages pull from historic maps, vernacular photography, stereoscope images and their marketing, and contemporary cyanotype prints. I had not done digital collaging before this project, so this was also a learning experience from a technological perspective.

My interest in a photography-based project started with our class visit to the Wisconsin State Archives. The delight I saw in the women from the 1905 album on their visit to Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake made me consider the infrastructures which enabled their visit — trails, highways, the railroad — and the politics of ownership which supported their visitation over others.

The women’s experience at Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake was grounded in playfulness and friendship, and so I did want to keep that energy within these collages. But, just as the sterographs show two of the same images, I wanted to be sure to include repetitive motifs to suggest that there are other sides to this story: the displacement of the Ho-Chunk and their sacred use of the site; disruption of places for wildlife to thrive because of an increase in the human presence; emerging social and political structures which push leisure to rural, wild landscapes and thus support imaginary, mythological narratives about the natural world and our supposed division from it. In these collages I want to celebrate the women’s joy while also recognizing the layered contexts which situate Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake as a site of many experiences, facilitated by a myriad of social, cultural, political, and material means.

The women’s experience at Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake was grounded in playfulness and friendship, and so I did want to keep that energy within these collages. But, just as the sterographs show two of the same images, I wanted to be sure to include repetitive motifs to suggest that there are other sides to this story: the displacement of the Ho-Chunk and their sacred use of the site; disruption of places for wildlife to thrive because of an increase in the human presence; emerging social and political structures which push leisure to rural, wild landscapes and thus support imaginary, mythological narratives about the natural world and our supposed division from it. In these collages I want to celebrate the women’s joy while also recognizing the layered contexts which situate Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake as a site of many experiences, facilitated by a myriad of social, cultural, political, and material means.

Finally, I want to add that I have been thinking about these collages with the writings of Keith Basso’s Wisdom Sits in Places, Bill Cronon’s “How To Read a Landscape,” and Clifford Geertz’s “Thick Description” from The Interpretation of Cultures. In all of these, I take away a sense of ongoing conversations, and how they are maintained through place-based oral narratives, landscapes, and cultural practices. With these collages, I hope viewers will get a sense of the Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake and how methods for visually describing it, and one’s experiences there, have changed through time.

Finally, I want to add that I have been thinking about these collages with the writings of Keith Basso’s Wisdom Sits in Places, Bill Cronon’s “How To Read a Landscape,” and Clifford Geertz’s “Thick Description” from The Interpretation of Cultures. In all of these, I take away a sense of ongoing conversations, and how they are maintained through place-based oral narratives, landscapes, and cultural practices. With these collages, I hope viewers will get a sense of the Tewakącąk/Devil’s Lake and how methods for visually describing it, and one’s experiences there, have changed through time.