It all started with a conversation at the Memorial Union.

In 1956, Henry Hart, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, invited his colleague Arno Lenz from civil and environmental engineering to join him for lunch and an idea. Hart proposed a cross-disciplinary course on river basin planning — a forward-thinking response to how water resource decisions were often made within artificial political boundaries, rather than guided by the realities of the physical environment.

Did You Know?

There have been 843 total WRM graduates as of spring 2025.

Both men had worked for the Tennessee Valley Authority, a pioneer in large-scale watershed management. They knew the limitations of siloed thinking. Lenz agreed to the proposal, and in 1958, the first river basin planning seminar launched, cross-listed in both of their departments. Students chose a topic within the realm of water resources management and developed individual research reports — a traditional seminar model, but one that began pulling in faculty from across campus, including law, urban and regional planning, and more.

The seminar became a seed. At a national water conference in 1962, Lenz heard growing momentum around interdisciplinary water programs at other universities. Energized, the UW seminar committee drafted a proposal for a new Water Resources Management (WRM) master’s degree. It was approved in 1965, laying the foundation for what would become one of the nation’s earliest and most respected interdisciplinary environmental programs.

“We’ve been able to sustain 60 years of this integrated interdisciplinary focus on water resources management,” says Ken Genskow, current WRM program chair. “Students take away real world experiences as part of their education, and that’s helped them secure positions in different agencies and organizations.”

Building the program took both vision and resources. Hart, Lenz, and fellow professors Fred Clarenbach (political science), Jake Beuscher (law), and Gerard Rohlich (engineering) secured a major training grant from the U.S. Public Health Service. Enrollment surged. The grant funded students, supported supplies, and enabled program administration to grow.

As word spread, faculty from an expanding range of disciplines — agricultural economics, botany, journalism, limnology, soils — joined the effort. So did students from all kinds of academic backgrounds and career paths, creating a learning environment enriched by diverse perspectives and real-world experience.

In 1970, the newly established Institute for Environmental Studies (now the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies) offered the WRM program a broader academic home — joining the institute in 1972 and anchoring itself in an interdisciplinary community and serving as a blueprint for future professional degree programs.

The focus on delivering upon the needs of a client — in our case, Monroe, Vernon, and La Crosse Counties — forces students to reckon with the social and political dynamics that interact with what can otherwise be a straightforward research question.

— Jackson Parr, WRM ’20

The early federal funding didn’t last. In 1975, amid economic downturn and growing federal deficits, the Nixon administration cut the training grants that had supported WRM’s growth. But even without robust financial backing, the program thrived. Applications continued to climb.

By then, the seminar model had evolved into something new. In 1971, the WRM program was presented with a complex, real-world project: the federal relicensing of the Chippewa Flowage dam in northwestern Wisconsin. Originally constructed in 1924, the dam was up for review, and its impacts — ecological, social, political — were the subject of intense debate. WRM students worked for two years alongside state agencies, utilities, tribal nations, and local communities to investigate and document the issues. They traveled to Washington, D.C., to present their findings before the Federal Power Commission.

That experience reshaped the WRM model. Practicum workshops became a cornerstone of the program— team-based projects where students tackle pressing water and environmental challenges for real clients. It’s a model that has endured for over five decades.

Where has WRM been? Check out an interactive map showing locations and summaries of every practicum project.

“The very first semester [the students] are here, they begin learning about what their project will be, and how they will meet the needs of local stakeholders and partners while also addressing their own interests that they came to graduate school to study. They’re not just handed a research project. They really have to, as a group, define the parameters of that research project that’s then applied to the needs of a community,” says Genskow.

Now celebrating its 60th year, the WRM program continues to ripple outward. Dozens of communities have benefited from WRM practicums, and hundreds of graduates have gone on to shape water policy, steward ecosystems, and build bridges across disciplines.

“The WRM program really exemplifies the Wisconsin idea because it works with communities on real-world watershed issues. Each cohort of WRM students acts as a consulting firm — coming up with management recommendations and writing a report,” says Jim Miller, Nelson Institute graduate program manager.

Students in the WRM program gain a well-rounded education that combines breadth with flexibility, allowing them to tailor their studies to their individual interests and career goals. The two-year program requires nine credits in science, nine credits in human dimensions, six credits in analytical tools, and 15 credits in a self-selected area of specialty, giving students both a strong foundation and the freedom to shape their degree around their professional aspirations.

Looking back to the program’s beginnings, interdisciplinarity remains its strongest draw — attracting applicants from around the world who bring a wide range of backgrounds and perspectives. “The program looks for leaders and hard workers — people who are motivated, dependable, reliable, and mature,” Miller says.

As an undergrad, I had a lakes and watershed management professor who pointed me towards the WRM program. He said there was no other place like UW-Madison — the birthplace of limnology — where you could study surrounded by water and then go enjoy a beer out on the Terrace. I needed no more convincing.

— Paul Dearlove, WRM ’96

Looking forward to the program’s future, Genskow cites advancing technologies as the touchstone for managing water resources. “There’s more data available, more analytical tools for rapidly processing that data, new kinds of environmental monitoring that can provide real time information to work with, and more public access to these kinds of democratized tools with the need for someone to help interpret them.” Genskow says. “So more of the same, but in a really amplified way.”

What began as a lakeside conversation between two professors is now a legacy — one that flows through every student, stakeholder, and watershed it touches.

By the Numbers

Check out these interesting stats about the WRM practicum experiences.

32

Focused on watersheds

10

Focused on a lake

4

Supported a county government

4

Had a statewide focus

4

Were on the UW-Madison Campus/Arboretum

3

Partnered with a Wisconsin Tribal Nation

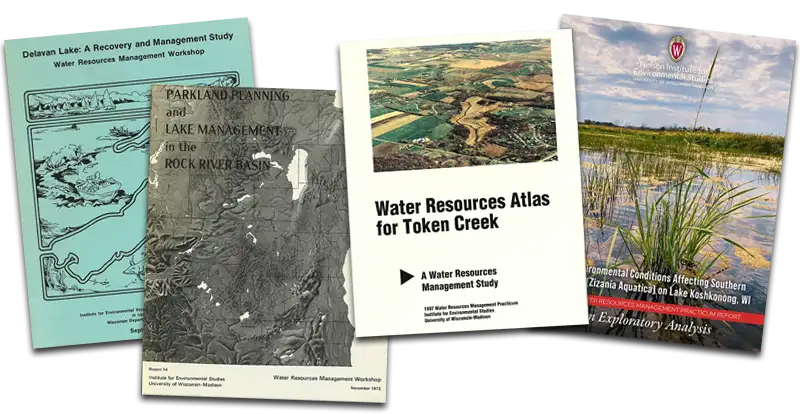

WRM Reports

See every water resources management practicum report cover, starting in 1971.

History of WRM Chairs

Ken Genskow

2024-present

Anita Thompson

2015-2023

Ken Potter

2007-2015

Linda Graham

2004-2007

Fred Madison

1999-2004

Jean Bahr

1995-1999

Ken Potter

1992-1995

Dave Mickelson

1990-1992

Steve Born

1988-1990

Erhard Joeres

1984-1988

Steve Born

1983-1984

Erhard Joeres

1980-1983

Henry Hart

1977-1980

Dave Stephenson

1975-1977

Charles Falkner

1974-1975

Dave Stephenson

1968-1974

Fred Clarenbach

1965-1968